By Alka Tripathy-Lang, Ph.D (@DrAlkaTrip)

Delhi’s citizens anxiously await a bigger shock during an ongoing swarm-like earthquake sequence, though swarms rarely include a larger event.

Citation Tripathy-Lang, Alka, (2020), Don’t panic, prepare! Delhi earthquakes remind citizens of risk, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.096

On April 12, 2020, just over two weeks into India’s lockdown forced by the spread of COVID-19, denizens of New Delhi were startled by the unfamiliar rocking of a small magnitude-3.5 earthquake. Delhi usually pulses with movement as the city’s dense population mills about, but these background vibrations were largely absent when the earthquake struck on a Sunday afternoon. Coupled with the fact that this earthquake ruptured a mere 5 miles (8 kilometers) below the surface, many people reported feeling the quake’s waves to various organizations that track earthquakes, such as the European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre (EMSC) and the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Since then, the area around New Delhi has been lightly jostled by several additional earthquakes felt by some of the populace, including a magnitude-3.4 quake on May 10, a magnitude-4.5 earthquake on May 29, and a shallow magnitude-3.0 event on June 3. An additional 14 temblors ranging from magnitude-1.8 to magnitude-3.0 struck the region around Delhi between April 12 and June 11, according to B K Bansal, director of the National Center for Seismology (NCS) in India.

*An additional magnitude-4.7 earthquake struck southwest of Delhi the evening of July 3. Felt reports streamed into the EMSC database, with 52 Delhiites describing sensations ranging from shaking to swaying.

*timeline of felt earthquakes updated on Saturday, July 4 at 1:00 a.m., local time, to reflect the latest event in the region around Delhi

In spite of various news sources suggesting a large earthquake is imminent, Bansal says, “We looked at the Delhi earthquake data of [the] last two decades, [and] no definite pattern is observed in frequency of earthquake occurrence.” In other words, given the past earthquake history of the Delhi region, the recent observed seismic activity is not unusual.

This behavior is best characterized as ‘swarm-like’. An earthquake swarm comprises mostly small tremors, according to the USGS, and can continue for days or even months. Swarms typically lack a mainshock, although recent quakes in Puerto Rico initially exhibited swarm-like behavior, but then became an earthquake sequence with a magnitude-6.4 mainshock and several significant aftershocks. However, in India, past swarms near Delhi did not precede major earthquakes or cause widespread destruction.

In a press release dated June 11, Bansal said not to panic. He told Temblor, “There is no scientific technique available to forecast [an earthquake] in advance with reasonable degree of accuracy in time, magnitude and location.” The lesson? Ignore the fear mongers, and instead, prepare for future earthquakes.

Click on the questions below to jump to the relevant sections, or read on below.

Delhi’s geology: why it matters

Delhi’s inhabitants: earthquake preparation

Old rocks and young sediment

Geologists loosely classify the rocks upon which Delhi sits into two categories. The first group consists of rocks more than one billion years old, made almost entirely of quartz. These incredibly strong rocks form a high-standing ridge in the south-central region of the National Capital Territory around Delhi, says Bansal.

The second category, called alluvium, varies in thickness from approximately 33 feet (10 meters) to more than 984 feet (300 meters), according to Bansal. Sourced from rivers draining the nearby Himalaya, much of the alluvium consists of unconsolidated sediments, meaning that the loosely packed deposits have not yet become a bona fide rock.

When surface waves—the most damaging seismic waves produced in an earthquake—enter sediments such as alluvium, “the waves slow down and increase in amplitude (size) so that you shake harder, and for a longer period of time,” according to Wendy Bohon, an earthquake scientist at the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS).

Alluvium buried deep below the surface behaves more like rock, and does not pose a hazard. Alluvium closer to the surface, though can present a problem, seismically speaking.

Excerpt from IRIS animation showing how surface waves propagate through solid bedrock, poorly consolidated sediment, and water-saturated sand and mud. The sediment slows and amplifies the waves, and the water-saturated surface is prone to liquefaction. Credit: IRIS

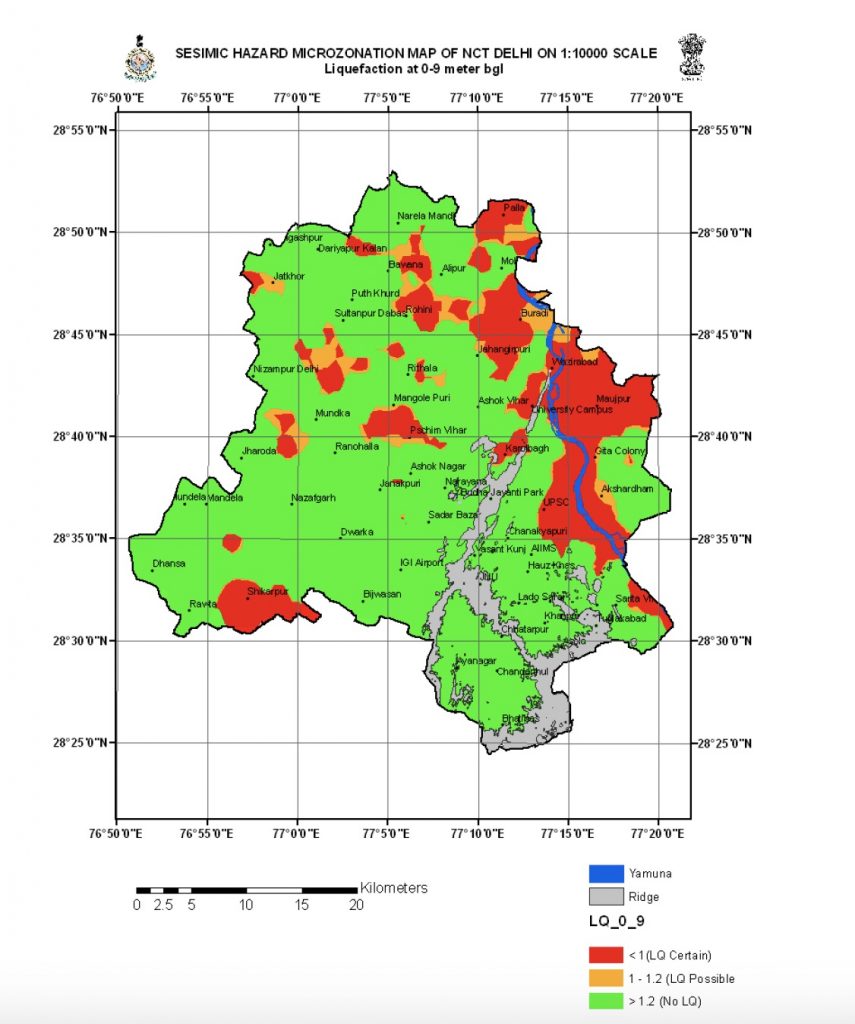

The alluvium of the Yamuna River on the east side of Delhi and pockets of the western Najafgarh flood plain poses the most serious shaking risk, says Bansal. Not yet a rock, this water-logged alluvium is also susceptible to “liquefaction.” Liquefaction occurs when loosely packed, wet sediment loses its strength and stability in response to ground shaking, according to the USGS, just like when you wiggle your toes in wet beach sand. If the ground upon which a building sits succumbs to liquefaction, major damage often results. The banks of the Yamuna River and parts of the Najafgarh flood plain are most prone to this hazard.

Faults slicing northern India

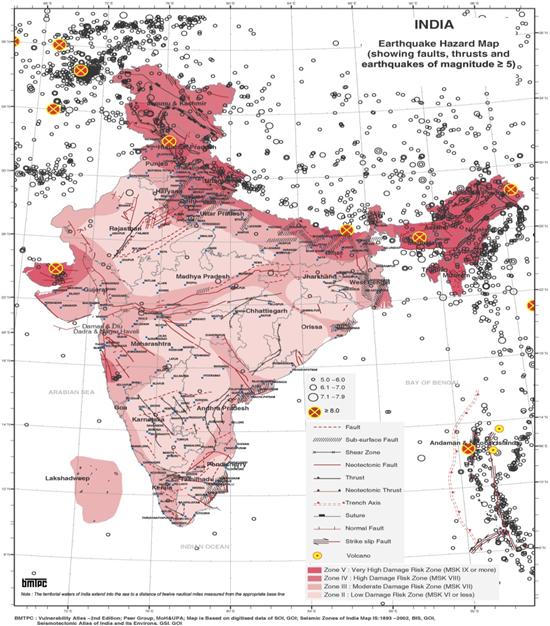

Bansal points out that several active fault systems traverse Delhi, trending in different directions. Significant earthquakes that occurred along faults in the southern part of the National Capital Territory include a magnitude-6.5 quake in 1720, a magnitude-6.7 earthquake in 1956, and a magnitude-6.0 quake in 1960, according to the Delhi microzonation report.

The earthquake swarm currently shaking Delhi mimics previously well-documented seismic activity. For example, a swarm rumbled the Sonipat and Rohtak areas in the northwest sector of the Delhi region from 1963-1965, illuminating faults hidden under thick sediments (Kamble and Chaudhury, 1979). From Dec. 2003 to Jan. 2004, another swarm occurred near Jind, also in the northwestern Delhi region. This swarm included 152 tremors, the largest of which was magnitude-3.4, according to Shukla et al. (2007). Neither of these swarms led to larger earthquakes within or near Delhi.

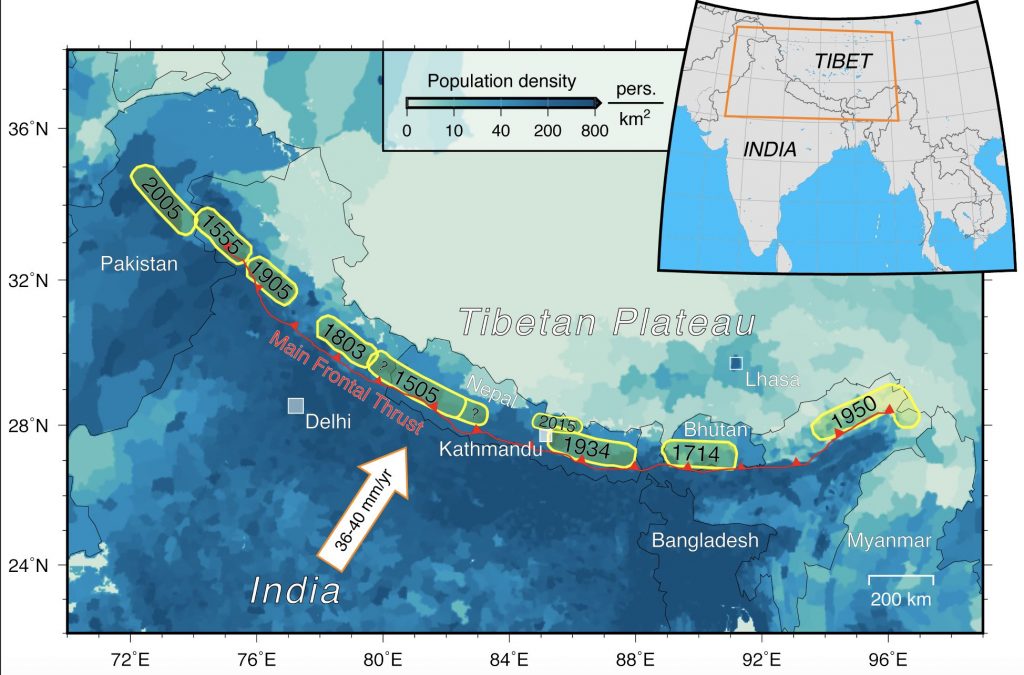

Himalayan faults, especially the Main Himalayan Thrust that is the interface between the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates, can produce earthquakes that release substantially more energy than Delhi’s local fault systems, with faults at the foot of the range breaking the surface less than 120 miles (200 kilometers) northeast of Delhi.

Sections of the Main Himalayan Thrust are “seismically locked,” according to a recent study, meaning that the fault is stuck in some places, even as the plate as a whole continues to move northward. Lead author Luca Dal Zilio, of Caltech, says that segments of the plate interface closest to Delhi have been seismically quiet, with the last major earthquakes occurring in 1803 and 1505. Dal Zilio says, “I personally believe that the seismic gap in the region of the 1803, and, in particular, the 1505 event are the most important ones because [they] are close to Delhi, are capable of generating large events, and [have] not [experienced] any large earthquakes over the last two centuries [or longer].” A large quake in the Himalaya near Delhi would almost certainly rattle the region, and depending on size and proximity, could have significant consequences for the population.

Dal Zilio points out that to release the energy built up along the locked section of the plate interface nearest Delhi, a very big quake—bigger than the 1803 event—must occur. This energy has been building up for centuries, potentially priming the Central Himalaya near Delhi for a very large earthquake.

Because of these active faults both near and far, coupled with high population density and infrastructure in and around Delhi, the Bureau of Indian Standards placed Delhi squarely in Seismic Zone IV out of five possible zones. Regions in Seismic Zone IV expect to experience severe shaking in the largest plausible earthquake scenario.

Earthquake preparedness

Perhaps the most long-lasting form of earthquake preparation is advocating for earthquake-resistant construction of new buildings, and retrofit of pre-existing structures. The Indian government’s Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs issued Model Building Bye-laws in 2016, which are recommendations for both new building construction and retrofit of existing structures for state and union territories, as well as urban local governments. “These bye-laws recommend compliance to the National Building Code prepared by the Bureau of Indian Standards, and [adherence] to building practices required for [India’s] seismic zone categories,” says Durga Shankar Mishra, Secretary of the Ministry of Urban and Housing Affairs. “Most of the states, union territories and municipal bodies have aligned their bye-laws accordingly,” he says, and those entities are responsible for enforcement.

However, as an individual or family unit, you can protect yourself and your family by taking simple precautions as outlined by the National Disaster Management Authority, like preparing an emergency kit, bracing ceiling fixtures, and securing furniture to the walls or floor. Do not hang heavy decorations above beds and other places that people sit.

Although the safest place to be during an earthquake is outdoors and away from anything that can fall on you, this is impossible in many parts of Delhi, particularly during lockdown. If you are indoors, DROP to the ground, COVER by bracing yourself under heavy furniture like a dining table, and HOLD ON.

Avoid glass, mirrors, and anything that could fall on you. Most importantly, stay inside until the shaking stops. Do not run outside, as most injuries occur when people try to move elsewhere during the shaking, according to the NDMA. If you are outdoors, move away from the exits and exterior walls of buildings, if at all possible, and do not enter or go near damaged structures. Find high ground if you are near a beach or river bank, in case the quake causes the water to slosh back and forth in what’s called a seiche. If you are trapped under debris following an earthquake, the NDMA recommends whistling or tapping on pipes or walls instead of yelling. By yelling, you may inhale hazardous amounts of dust. Aftershocks are a common occurrence after major earthquakes, so be prepared for additional shaking that may exacerbate already precipitous conditions.

In the event of a major earthquake, Bansal says people should go to the National Center for Seismology website or app for earthquake information. For instructions on what to do in the event of a quake, however, people should check the National Disaster Management Authority website for guidance.

**Editorial note – all magnitudes are reported from the Indian National Center for Seismology website, and may differ from magnitudes reported by the EMSC and/or USGS.

Further reading

Dal Zilio, L., Jolivet, R., and van Dinther, Y. (2020). Segmentation of the Main Himalayan Thrust illuminated by Bayesian inference of interseismic coupling. Geophysical Research Letters, 47, e2019GL086424. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086424

Kamble, V. P., and Chaudhury, H. M. (1979), Recent seismic activity in Delhi and neighbourhood, Mausam, v. 30, p. 305-312.

López, A.M., Hughes, K.S., & Vanacore, E. (2020), Puerto Rico’s Winter 2019-2020 Seismic Sequence Leaves the Island On Edge, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.064.

López, Alberto M., Elizabeth Vanacore, K. Stephen Hughes, Gisela Báez-Sánchez, and Thomas R. Hudgins (2020), Response and initial scientific findings from the southwestern Puerto Rico 2020 Seismic Sequence, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.068

Schmidt, Jennifer (2019), Gorkha aftershocks reveal seismic hazard in Nepal, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.058

Shukla, A. K., Prakash, R., Singh, R. K., Mishra, P. S., and Bhatnagar, A. K. (2007), Seismotectonic implications of Delhi region through fault plane solutions of some recent earthquakes, Current Science, v. 93, p. 1848-1853.

Singh, R. P. (2020), Pandemic lockdown sensitizes New Delhi to earthquake risk, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.087

Tripathy-Lang, Alka (2020), Slow moving fault pieces may limit large Himalayan quakes, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.079

- Living through the Loma Prieta earthquake - October 21, 2021

- The Great Quake Debate: an interview with seismologist and author Susan Hough - August 27, 2020

- Salton Sea Swarm quiets down - August 12, 2020