Oregon is susceptible to shaking from both shallow crustal earthquakes and large-magnitude subduction zone shocks. In either scenario, the population of Portland would be at risk.

By Alice R. Turner, Ph.D., Science Writer (@SeismoAlice)

Citation: Turner, A., 2023, Portland’s seismic hazards stem from subduction zone, local faults, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.315

When people think of earthquakes in the continental U.S., they often think of California. But Oregon — and particularly the city of Portland — also lies in the heart of earthquake country, where the seismic hazard comes from both the Cascadia Subduction Zone and shallow crustal faults within and around the city.

The big one

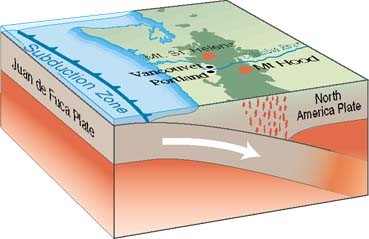

The Cascadia Subduction Zone is a 600-mile-long (1,000-kilometer) plate boundary where the oceanic Juan de Fuca Plate dives beneath the North American continent. This subduction zone has been relatively quiet and unassuming for the past three centuries, with little recorded seismicity. But in the 1980s, scientists realized that this quiescence may be foreboding. Scientists have found multiple lines of evidence confirming that the Cascadia Subduction Zone could host the most destructive type of earthquake — a so-called megathrust event.

Paleoseismologists have carefully analyzed marine and land sediments, finding evidence of between 19 and 20 magnitude-9 earthquakes in the last 10,000 years. “Right now, we’re possibly at the tail end of a cluster of five events that started 1,500 years ago, and they’re about 350 years apart,” says Cascadia expert Chris Goldfinger, an earthquake geologist at Oregon State University. “The last one we had was in 1700.”

The close one

Although a possible Cascadia megathrust earthquake has been the headliner when it comes to coastal Oregon’s seismic hazard, it is not the only fault in the region that could cause destruction. Many active faults are scattered around and beneath Portland. These faults also result from the plate boundary. The Juan de Fuca Plate is not colliding with the North American continent head-on. Instead, its motion results in clockwise rotation as it subducts, which is mostly accommodated within the overriding North American Plate by local, shallow crustal faults.

For instance, the Gales Creek Fault hosted earthquakes “roughly 1,000 years ago, 4,000 years and about 8,000 years ago,” says Ashley Streig, a professor at Portland State University and a co-author of a recent study about this local structure. From the 45-mile (72-kilometer)-long surface expression of the fault, the research team estimated the fault could produce magnitude-7.2 earthquakes. This active fault lies a mere 22 miles (35 kilometers) west of Portland.

Other faults, like those within Portland, are less well studied. The Portland Hills Fault, for example, runs through downtown Portland. But its especially hazardous location underneath the city cuts it off from scientists keen to study it, resulting in a lack of information about past earthquakes. However, because this and other urban faults have the same northwest orientation as well-studied faults outside the city, scientists can infer that stresses from plate motion are distributed among them. As a result, says Streig, “other structures near the Portland metro area are also likely to be a seismic hazard.”

Different faults, different feel

Both how an earthquake feels to people and the damage that it could cause depend on the distance from the fault that ruptured.

“When we talk about seismic hazard and the Pacific Northwest, particularly in Oregon, I’ve noticed that the focus is on the ‘big one,’” says Streig. The crustal faults have less frequent, smaller-magnitude earthquakes than the subduction zone, and so have a lower hazard. But they are close by, and “they shouldn’t be ignored,” she says.

If an earthquake ruptures very near or even directly beneath the city, the ground shaking of even moderate-magnitude events could be short but intense, with little warning. This means little — or zero — time to take protective action.

“You won’t have time to react,” says Goldfinger. “Usually by the time you figure out what’s going on, it’s over.”

A megathrust earthquake scenario presents a different risk. Shaking would last between 5 and 7 minutes. However, such a rupture would likely be near the coast — more than 50 miles (80 kilometers) from Portland. These 50 miles would act as a buffer because the amplitude of seismic energy would decrease as the seismic waves travel inland. “A megathrust earthquake for [Portland] will be a little more gentle [than a local event], ” says Streig.

The seismic energy from the earthquake would be detected via seismometers close to the fault well before it reaches Portland, which means city dwellers could have up to a minute of warning to take protective action before the shaking starts.

Preparing for the next earthquake

Whether or not the next earthquake is the big one or a close one, more than 2 million people live in the Portland metropolitan area, many of whom would be at risk in either scenario. There would be more than 18,000 fatalities in Oregon from the tsunami caused by a subduction zone earthquake alone. The Cascadia Region Earthquake Workgroup also forecasts direct and indirect economic losses could exceed $70 billion.

Yumei Wang, an engineer and geologist, has spent her career tirelessly working to influence policy to mitigate the damages that would come with a Cascadia earthquake.

Wang’s work began with schools. “Children are mandated to go to school. They should go to school in a safe building and come home every day whether there was an earthquake or not,” she says. After 12 pieces of legislation over 10 years, in 2009, Oregon launched the nation’s first state-funded seismic rehabilitation grant to help schools and emergency response facilities become seismically safe. In 2019 alone, $200 million was given in grants through the seismic rehabilitation grant program to retrofit schools and emergency buildings.

Lifeline infrastructure came next. After an earthquake, survivors should not need to worry about water — whether for drinking, taking showers or flushing toilets — yet safe water is often one of the biggest concerns following large earthquakes. Following six years of advocacy, the Oregon Health Authority now mandates seismic vulnerability studies for public water systems.

The most recent effort, in which Wang is involved, focuses on bulk fuel tanks located on liquefiable soils along the edge of the Willamette River that could cause a devastating spill and fire disaster when an earthquake strikes. Just last year, a bill was passed that now requires seismic vulnerability studies and mitigation.

The legislation is now institutionalized and self-sustaining. “Nobody needs to continue to fight for oversight and funding, legislative session after legislative session, to ensure progress on safety,” says Wang.

But there is still work to be done. In 2016, the Bureau of Development Services reported that Portland has more than 1,600 unreinforced masonry buildings that are highly vulnerable to collapse. Estimates suggest that less than 20 percent of these buildings have been either demolished or retrofitted (either fully or partially). Older bridges are also expected to suffer seismic damage in a major earthquake. Portland has 12 bridges that span the Willamette River, 10 of which were built before 1994, and have a higher risk of significant or moderate damage in an earthquake. As of this writing, the Pioneer Courthouse is the only building in downtown Portland that has basal isolation, an expensive retrofitting of the foundation that lets the building sway in an earthquake, not only preventing collapse, but also making the building safe immediately after an earthquake.

Portland is becoming more prepared for an earthquake, but it’s not there yet. “It is actually doable,” Goldfinger says. “Spending a lot of money is what it is going to take.”

For more on how to retrofit your single-family home, check out this document from the Oregon Seismic Safety Policy Advisory Commission. And for more information about Oregon’s risk from earthquakes and tsunamis, whether you live in earthquake country or just visit it, check out the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries’ reports on individual counties and even communities here.

References

Horst, A. E., Streig, A. R., Wells, R. E., & Bershaw, J. (2021). Multiple Holocene Earthquakes on the Gales Creek Fault, Northwest Oregon Fore-Arc. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 111(1), 476–489. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120190291

Walton, M. A. L., Staisch, L. M., Dura, T., Pearl, J. K., Sherrod, B., Gomberg, J., Engelhart, S., Tréhu, A., Watt, J., Perkins, J., Witter, R. C., Bartlow, N., Goldfinger, C., Kelsey, H., Morey, A. E., Sahakian, V. J., Tobin, H., Wang, K., Wells, R., & Wirth, E. (2021). Toward an Integrative Geological and Geophysical View of Cascadia Subduction Zone Earthquakes. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 49(1), 367–398. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-071620-065605

Copyright

Text © 2023 Temblor. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

We publish our work — articles and maps made by Temblor — under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license.

For more information, please see our Republishing Guidelines or reach out to news@temblor.net with any questions.

- Earthquake science illuminates landslide behavior - June 13, 2025

- Destruction and Transformation: Lessons learned from the 2015 Gorkha, Nepal, earthquake - April 25, 2025

- Knock, knock, knocking on your door – the Julian earthquake in southern California issues reminder to be prepared - April 24, 2025