By David Jacobson, and Volkan Sevilgen Temblor

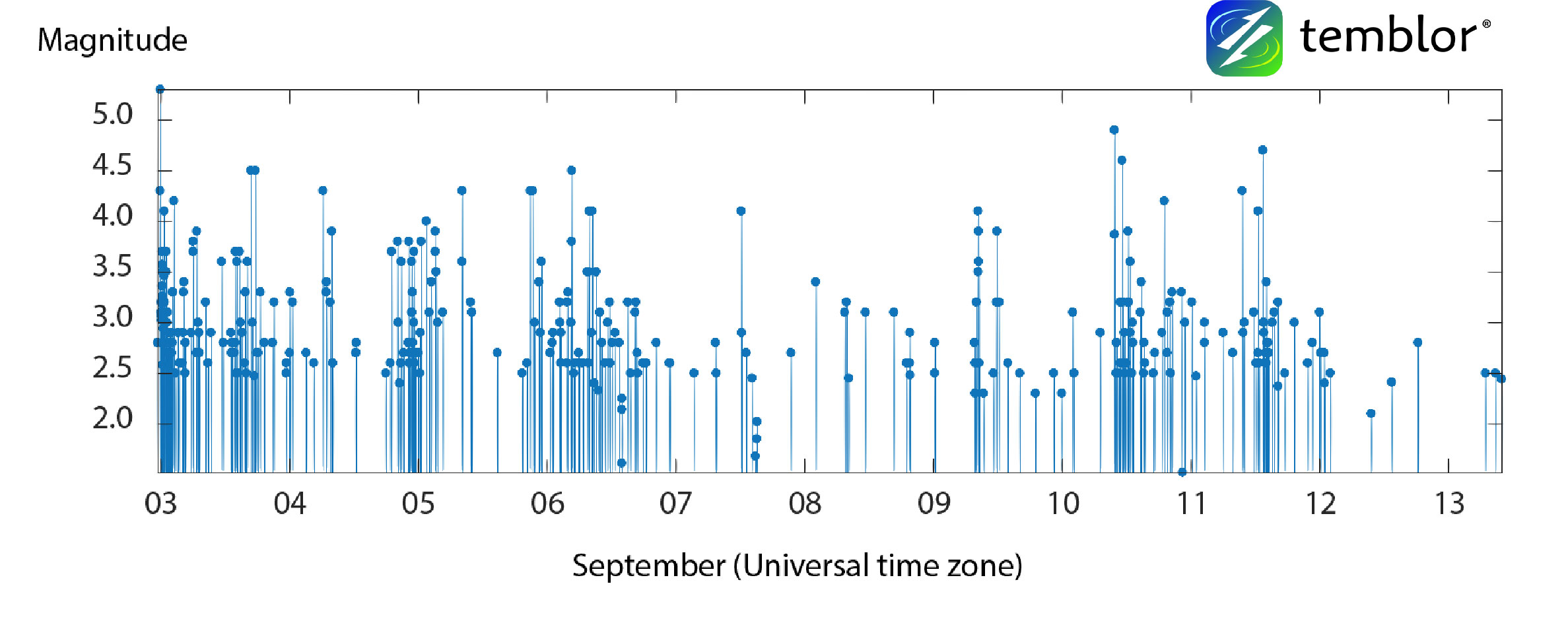

Over the last eleven days, an earthquake swarm has been shaking southeastern Idaho, near the city of Soda Springs. The swarm kicked off with a M=4.1 on September 2 and was followed 1:24 later by a M=5.3. In total, over 300 have struck the region, none of which have caused damage, though local news outlets are reporting that residents of the area are growing wary. The M=5.3 quake on September 2 garnered over 2,000 felt reports on the USGS website, and cause some Soda Springs residents to duck for cover. Even though the rate of earthquakes is decreasing in the area, and it is possible that this swarm could continue to die out over the next couple weeks, because swarms can precede larger events, we thought we’d take a closer look.

This part of southeastern Idaho is within the Intermountain Seismic Belt (ISB), a, 1300 km-long zone of seismicity extending from southwestern Utah to northwest Montana. Almost all of the faults in this zone are extensional in nature, though some show strike-slip motion. This extensional faulting has formed characteristic valleys, which are bounded on one of both sides by normal faults. Some people believe that earthquakes within the Intermountain Seismic Belt could be related to the extension of the Basin and Range, and to Yellowstone Hot Spot. The Wasatch Fault, which runs underneath Salt Lake City is part of this seismicity belt, as is the Bear Lake Fault Zone, which is where the seismic swarm in Idaho is currently taking place. While the M=5.3 quake less than two weeks ago was large enough to cause some panic among residents, this quake and associated aftershocks should not be considered surprising. The Global Earthquake Activity Rate (GEAR) model, which is available in Temblor and takes into account global strain rates and the last 40 years of seismicity, shows that for this part of Idaho, near the town of Soda Springs, a M=5.25+ earthquake is likely in your lifetime.

While none of the earthquakes in this swarm have been large enough to cause damage, the region is susceptible to experiencing large magnitude quakes along the Bear Lake Fault Zone, just east of Soda Springs. For example, in 1884, a M~6.3 quake shook the region. Because of the low population density of the area, and the simple wood construction of houses almost no damage was reported. However, should a similar or larger earthquake occur, which the USGS says is possible, damage could be significant. In the USGS scenario catalog, they estimate that the Eastern Bear Lake Fault could rupture in a M=7.3 earthquake, highlighting the importance of understanding the earthquake risk in your area.

References

USGS

University of Utah

James P. Evans, Dawn C. Martindale, and Richard D. Kendrick, Jr., Geologic Setting of the 1884 Bear Lake, Idaho, Earthquake: Rupture in the Hanging Wall of a Basin and Range Normal Fault Revealed by Historical and Geological Analyses, Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 93, No. 4, pp. 1621–1632, August 2003

- Deep earthquake beneath Taiwan reveals the hidden power of the Ryukyu Subduction Zone - January 7, 2026

- Magnitude 7 Yukon-Alaska earthquake strikes on the recently discovered Connector Fault - December 8, 2025

- Upgrading Tsunami Warning Systems for Faster and More Accurate Alerts - September 26, 2025