By David Jacobson, Temblor

Over the last few weeks, North Korea has been in the news as they threaten to launch a nuclear missile towards the US territory of Guam. However, few people may know that as North Korea was conducting its nuclear tests on its home soil, a global network of seismometers detected the blasts, where the energy release of the detonation resembles moderate magnitude earthquakes. The last of these was on September 9, 2016, when a test was picked up as equivalent to a M=5.2 earthquake.

All five of the North Korea’s nuclear tests have taken place at Mount Mantap in northeastern North Korea, in the Punggye-ri nuclear test site. This isolated granitic mountain is approximately 85 km (50 mi) from the closest major city, and contains an intricate network of tunnels, into which the nuclear devices are placed. To this day, it remains the only active nuclear test site on earth.

Every time a test occurs, both independent seismometers, as well as ones placed as part of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, pick up seismic waves the same way they would an earthquake. Professor Paul Richards at Columbia University, an expert on monitoring underground nuclear explosions said that, “nuclear test explosions in North Korea are detectable down to just a few tons of TNT equivalent. That it to say, down to levels about three hundred times smaller than the first nuclear test explosion conducted in that country (on October 9, 2006).” While over 180 countries have signed this nuclear test ban treaty, North Korea has not, and while the US has signed it, it has not been ratified.

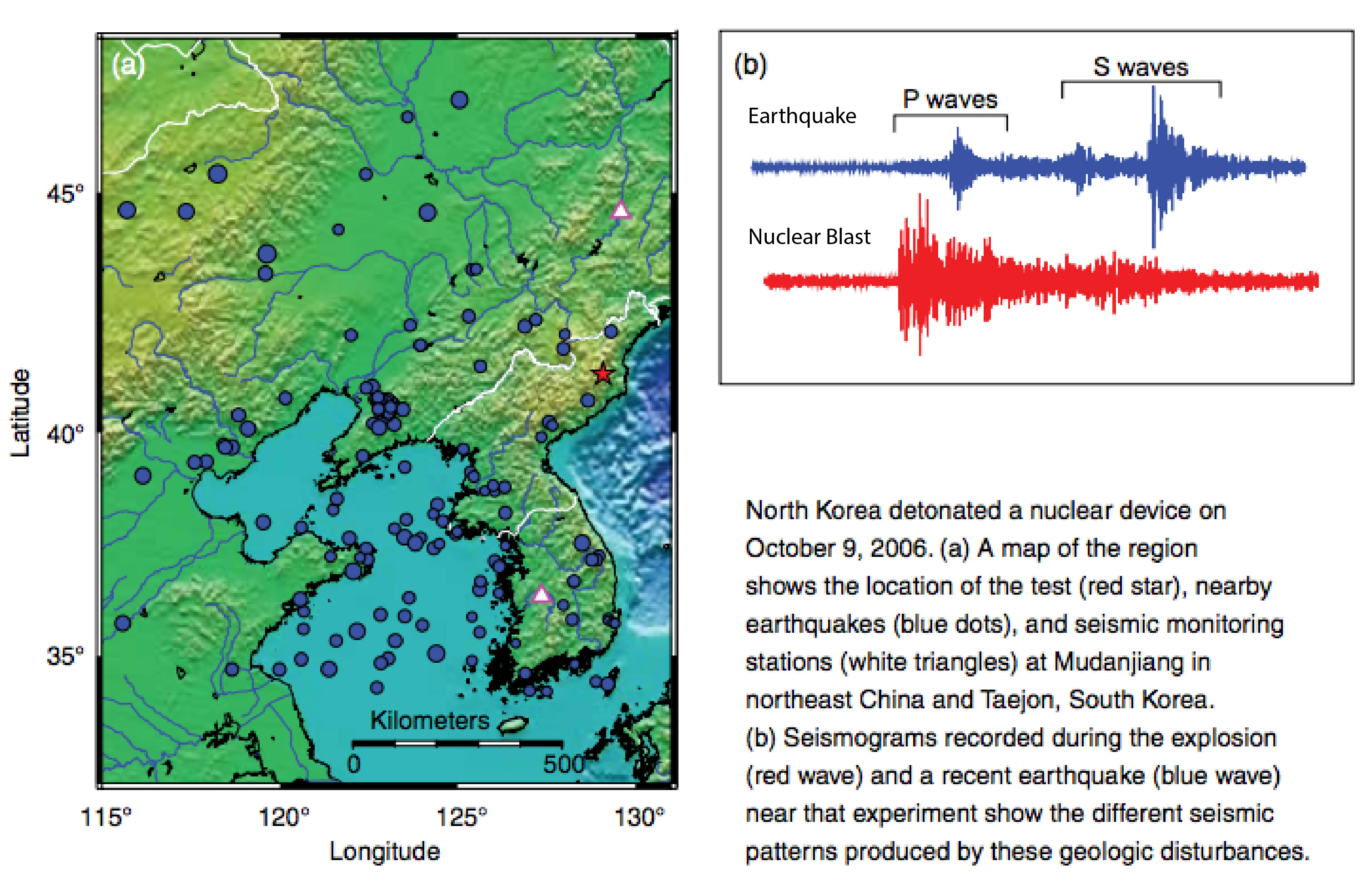

When seismic waves originate from a location like Mount Mantap, it is likely a nuclear test has taken place, as the region has a very low rate of natural (tectonic) seismicity. However, there are also clues in the seismic waves themselves, which forensic seismologists can use to confirm that the waves are from a nuclear blast. When an earthquake or nuclear blast occurs, several types of seismic waves are created, which travel at different speeds and have different characteristics. Primary waves (P-waves) are the first to arrive and are often only detectable by seismic stations. Secondary waves (S-waves) then arrive, and are characterized by their shearing motion. Finally, come the surface waves, including what are known as Rayleigh waves. In a natural seismic event, the amplitude of Rayleigh waves are larger than the P-waves. However, in a nuclear blast, the opposite is true. This, in addition to the fact that nuclear testing will often take place at extremely shallow depths is what scientists look for in determining whether an event was natural or man-made.

One of the reasons why seismic detection of nuclear blasts in North Korea is so accurate, and why it is capable of picking up events equivalent to a M=1.5, is ironically because of large recent earthquakes in China and Japan. Large earthquakes in these countries after the final round of negotiations of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty in the 1990s prompted both countries to install more seismic stations in order to quantify their seismic hazard even more. A byproduct of this is that many more man-made seismic signals can be picked up, including those from nearby North Korea. This has made for pinpoint accuracy of the locations of each nuclear test in North Korea. This has great importance as knowing the exact location of an underground test is vital to determining the size of the nuclear device. This highlights how the occurrence of natural events (earthquakes) has made detecting and analyzing man-made events that much more possible, impacting global political negotiations.

References

“How earthquake scientists eavesdrop on North Korea’s nuclear blasts” by Alexandra Witze, JULY 25, 2017, Science News – Link

Personal communication with Professor Paul Richards (Columbia University)

Paul G. Richards (2016) The history and outlook for seismic monitoring

of nuclear explosions in the context of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, The

Nonproliferation Review, 23:3-4, 287-300, DOI: 10.1080/10736700.2016.1272207

“Sleuthing Seismic Signals”, Science and Technology Review, March 2009, published by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

New York Times

ABC News

- Deep earthquake beneath Taiwan reveals the hidden power of the Ryukyu Subduction Zone - January 7, 2026

- Magnitude 7 Yukon-Alaska earthquake strikes on the recently discovered Connector Fault - December 8, 2025

- Upgrading Tsunami Warning Systems for Faster and More Accurate Alerts - September 26, 2025