Though September has seen a few big earthquakes in recent years, there is nothing special about the month.

By Manuel J. Aguilar-Velázquez (@ManuAguilar411), R. Daniel Corona-Fernández (@rdcoronaf), and Miguel Á. Rodríguez-Domínguez (@MiguelRodDom), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

Citation: Aguilar-Velázquez, M.J., Corona-Fernández, R.D., Rodríguez-Domínguez, M.Á, 2022, Is September really “earthquake month” in Mexico?, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.285

Este artículo también está disponible en español.

Mexico is a seismically active country. Since 2017, six earthquakes larger than magnitude 7.0 have struck the country — four during the month of September. The first, the magnitude-8.2 Tehuantepec earthquake, struck on Sept. 7, 2017. Less than two weeks later, on September 19, the magnitude-7.1 Puebla-Morelos earthquake occurred. The latter quake struck 32 years to the day after the magnitude-8.1 Michoacan earthquake. On Sept. 7, 2021, the magnitude-7.4 Acapulco earthquake rattled coastal Guerrero. Most recently, as if a tectonic joke, on Sept. 19, 2022, a magnitude-7.7 earthquake shook the Michoacan coast.

For most Mexicans, these recent events have solidified September as “earthquake month.” Mexican seismologists therefore face the challenging task of convincing people that this assumption is not true. A hard look at the data shows these repeated events for what they are: an unfortunate coincidence.

Mexico is vulnerable to earthquakes because it is uniquely situated near five tectonic plates: Cocos, North America, Pacific, Caribbean and Rivera. As the plates slowly push against, past, and away from one another, energy accumulates. When enough is stored up, a percentage of that energy is suddenly released, when the plates slip past one another, causing an earthquake.

Looking for answers in an earthquake catalog

To demystify the September coincidence is unique, we looked at a record of earthquakes that occurred in Mexico between 1787 and 2018. Records such as these come from collections of quality-controlled seismometer data, known as earthquake catalogs. In the catalog that we used, the magnitudes and epicenters of large earthquakes (magnitude-6.5 and larger) have been carefully revised from peer reviewed publications. We updated this catalog with information from earthquakes between 2019 and 2022, gathered from the Servicio Sismológico Nacional catalog (SSN, 2022).

We evaluated the catalog by looking at when earthquakes of magnitude-7.0 and larger struck and then repeating this for magnitude-6.5 and larger events. We assumed that all of the earthquakes of magnitude-7.0 and larger were recorded, and thus the catalog is “complete.” Consequently, the locations and magnitude estimations for those earthquakes are reliable. We do not have information about magnitude-6.5 to -7.0 earthquakes prior to 1900, however, since subsequent magnitude-6.5 and larger quakes have been carefully revised in the recent Sawires et al. (2019) publication, we consider these relevant as well. This approach gives us a large number of earthquakes to study even though we have no information for the magnitude-6.5 to 7.0 earthquakes occurred before 1900.

Over this time, earthquakes occurred throughout southern and western Mexico (322 magnitude-6.5 and greater events and 151 magnitude-7.0 and greater events). The Pacific coast, south of Puerto Vallarta, is particularly prone to shaking because the Cocos tectonic plate subducts beneath the North American Plate, causing large earthquakes.

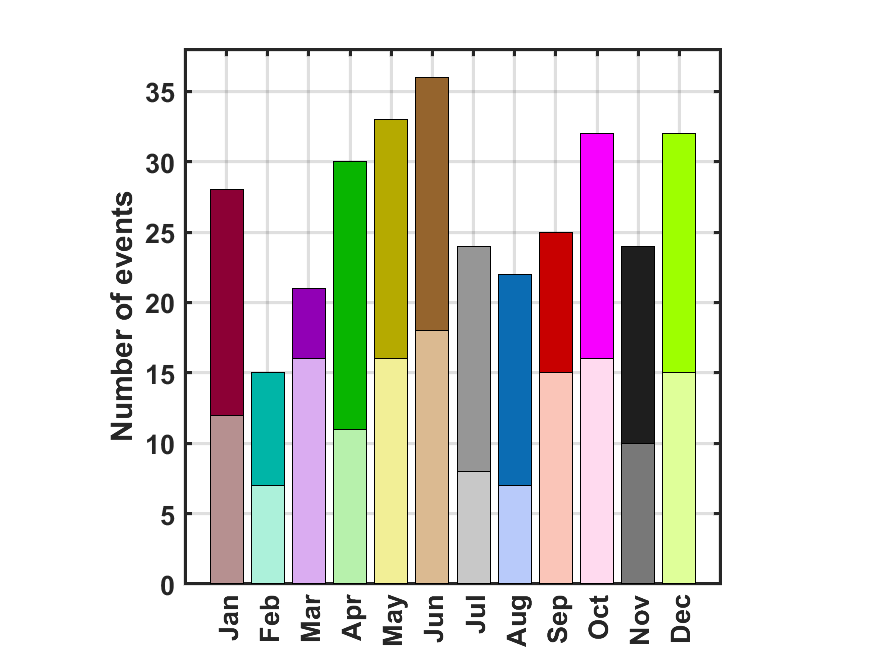

Our data show that earthquakes are not getting more frequent or bigger over time. Importantly, these data show that earthquakes do not occur more frequently in September.

Magnitude-7.0 and larger earthquakes occurred on 123 different dates; 79% of these dates had no coincidences, 20% had two-event coincidences, and 2% had three-event coincidences. This means that 26 dates of the year have seen more than one earthquake strike.

Magnitude-6.5 and larger earthquakes occurred on 212 different dates; 62% of these had no coincidences, 28% were two-event coincidences, 6% were three-event coincidences, 3% were four-event date coincidences, and only one day (June 7) had seven-event coincidences. This means that 80 days of the year have seen more than one earthquake strike. This larger result for the lower magnitude quakes is not surprising, as the greater the number of earthquakes considered, the larger the probability of having earthquakes with the same “birthday”.

According to our analysis, April and December have more date coincidences (11 and 10, respectively) than September (4). The latest large earthquake that occurred in December was in 2015, and most of the others took place in the middle of the 20th century. Following the “earthquake month” logic, during the 1950s, Mexicans would have, incorrectly, thought that December is the earthquake month. We observed something similar in April, with a magnitude-6.7 and magnitude-7.3 quake striking in 2002 and 2014 respectively. However, since they did not strike as close in time to one another, people do not remember April as “earthquake month.”

The data we observed clearly show that September (or any other month) is not a magic time when large earthquakes are likely to occur. The recent coincidences have created this collective idea. Furthermore, some of these events have affected Mexico City making the recent events easier to remember for more than 22 million people. Nevertheless, we need to remember that largest earthquakes may occur in several regions of Mexico.

Seismologists have only a short time span of records compared to the millions of years in which earthquakes have occurred within the current tectonic-plates configuration. If we had millions of years of data, we would probably observe a uniform distribution of earthquake occurrences in time. Regardless, Mexicans should be prepared for earthquakes, as many more will strike in the future.

References

Sawires, R., Santoyo, M.A., Peláez, J.A., Corona-Fernandez, R.D. An updated and unified earthquake catalog from 1787 to 2018 for seismic hazard assessment studies in Mexico. Sci Data 6, 241 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0234-z

México. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geofísica, Servicio Sismológico Nacional (2022), Catálogo de sismos, edited, UNAM, IGEF, SSN, https://doi.org/10.21766/SSNMX/EC/MX

- The Earthquake that Shook the South - February 26, 2026

- Introducing Coulomb 4.0: Enhanced stress interaction and deformation software for research and teaching - February 20, 2026

- Deep earthquake beneath Taiwan reveals the hidden power of the Ryukyu Subduction Zone - January 7, 2026