Ross S. Stein, Ph.D., Temblor Check your risk

The mysterious ‘Fontana Trend’ lit up in shallow and widely felt shocks during the past week, putting residents on edge. The swarm lies near the junction of the major Sierra Madre and San Jacinto Faults.

Citation: Ross S. Stein (2019), Seismic swarm in progress in Southern California, Temblor,

http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.027

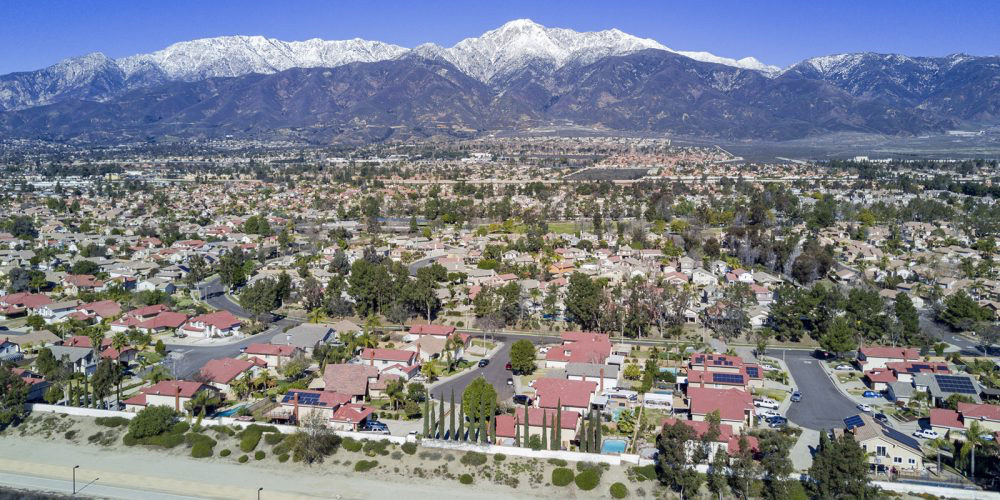

About 110 M≥1 earthquakes have struck in the past 10 days along a 5-km-long (3-mi-long) trend between Riverside and Rancho Cucamonga, near Fontana and Glen Avon. The quakes lie only 2-4 km (1.5-2.5 mi) below the ground, and are unusually shallow and so readily felt despite their small size. The largest three shocks during the past month have been just over M=3, and so do no damage. Their focal mechanisms indicate left-lateral faulting (whichever side you are on, the other side moves to the left, as indicated with the grey half-arrows in the map below). The swarm lies just beyond the end of an unnamed fault mapped by the California Geological Survey. The major San Jacinto Fault lies to the east, and the major Sierra Madre Fault lies to the north.

This isn’t the first time

The so-called ‘Fontana Trend’ (Gooding, 2007) of seismicity has persisted for at least 30 years, so far without producing damage. The largest earthquake on the trend in the past 20 years is M=3.8. This might indicate that the trend is caused by slip on a relatively young set of discontinuous fault patches, or that sediments flow into the basin faster than the fault slips, continuously blanketing the fault at the surface. In Upland, about 20 km (13 mi) to the northwest, a M=4.6 shock struck in 1988, and a M=5.2 struck in 1990, on a previously unknown left-lateral fault with a similar trend (Hauksson and Jones, 1991). So, there is no reason to presume that M=3.8 is the upper bound along the Fontana Trend.

A Ghost fault

A closer look at the topography (see the grey contours in the map below) hints at a possible fault etched into the landscape, but it could just as well be drainage coming off the hillside.

It all makes sense

Faults perpendicular to the right-lateral San Jacinto Fault would be expected to be left-lateral. Think of it this way: The entire area is being compressed in a north-south direction, and being stretched in an east-west direction. Place the crust, or a block of rubber, under these stresses, and faults oriented northwest like the San Andreas and San Jacinto will move right-laterally, faults oriented east-west like the Sierra Madre will undergo thrust motion, and faults oriented like the Fontana Trend should move left-laterally.

Hemmed in by freeways

While the cause of the swarm is unknown, generally swarms are thought to result from ‘fault creep,’ when faults become unstuck and slide rapidly for some period, perhaps lubricated by the release of fluids. There is an industrial settling pond just to the west of the swarm, and so it’s not impossible that industrial seepage played some role. Dr. Susan Hough at the USGS in Pasadena said to us, “Induced seismicity seems unlikely in this case. I wouldn’t imagine the settling pond affects stress in any significant way, even at shallow depths”. Seismic swarms often precede eruptions, but only rarely precede large earthquakes.

Gooding (2007) analyzed the consequences of a M=6.3 shock on the Fontana Trend, using the FEMA software, HAZUS. An earthquake of this size would not be unprecedented on an unknown fault (the 1994 M=6.7 Northridge shock struck on one), nor would it be surprising to seismologists. She found that 38,000 buildings would suffer some damage, and about 800 buildings would likely be destroyed. About half of the local hospital beds would be out of service for a week, and the total cost would come to about $3.5 billion.

Even though the swarm is more likely to fade than trigger a large quake, the Temblor Earthquake Score of this portion of the Inland Empire is high. That’s because it is close to three major faults capable of M≥7.5 earthquakes, and the sediment-filled basin amplifies the shaking and could partially liquefy in an earthquake.

So, if you live or work in this area, it would be wise to consider how you could lower your risk and that of your family.

References

Margaret L. Gooding (2007), Seismic Hazards of the Fontana Trend, M.Sc. dissertation, Manchester Metropolitan University (U.K.), http://www.goodingfamily.biz/images/MastersThesisPDF/Thesis_Gooding_Sept07sm.pdf

Egill Hauksson and Lucile M. Jones (1991), The 1988 and 1990 Upland earthquakes: Left‐lateral faulting adjacent to the central Transverse Ranges, J. Geophys. Res., 96, 8143-8165, https://doi.org/10.1029/91JB00481

USGS (2019), Quaternary Fault and Fold Database of the United States, Interactive Fault Map, https://earthquake.usgs.gov/hazards/qfaults/

USGS (2019), ANSS Seismic Catalog, https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/map/

- The Earthquake that Shook the South - February 26, 2026

- Introducing Coulomb 4.0: Enhanced stress interaction and deformation software for research and teaching - February 20, 2026

- Deep earthquake beneath Taiwan reveals the hidden power of the Ryukyu Subduction Zone - January 7, 2026