Ground motions in Los Angeles Basin show up to four times greater shaking than expected from the Ridgecrest earthquake.

by Laura Fattaruso, M.S., Ph.D. Candidate, UMass Amherst (@labtalk_laura)

Citation: Fattaruso, L., 2020, Ridgecrest quake shook tall L.A. buildings up to 4 times more than expected, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.151

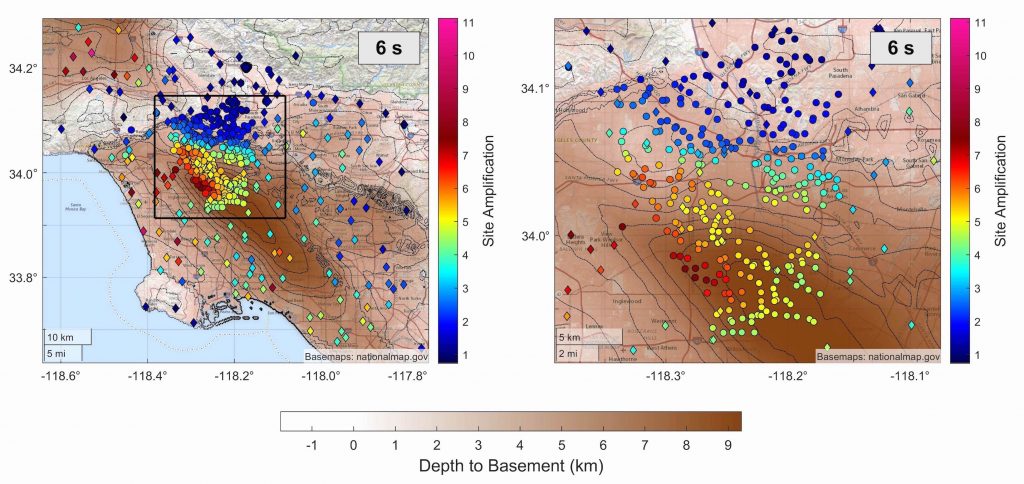

A network of over 500 sensors spread throughout Los Angeles picked up shaking during the July 6, 2019 magnitude-7.1 Ridgecrest earthquake. Though the epicenter was nearly 124 miles (200 kilometers) away, shaking was felt throughout downtown L.A. Data from those sensors has revealed that shaking was amplified by as much as four times the expected intensity in some parts of Los Angeles, according to a report just out in Seismological Research Letters.

“Observations recorded on that dense array allowed us to see variation in the ground shaking on a scale that has really never been observed before for a large earthquake like that in the L.A. Basin,” explains Monica Kohler, an earthquake engineer at Caltech and lead author of the report.

Los Angeles is like a bowl of jelly

Hazard assessments already consider shaking amplification from basins, but why some areas shake more than others is poorly understood. An often-used analogy to understand basin effects is a bowl of jelly — when shaken, the jelly wiggles more than the bowl. Los Angeles is built on a large, deep sedimentary basin that can amplify earthquake waves just like the jelly, especially the longer period ones that affect larger buildings and high-rises.

The authors of the study find that the factors most often considered in these hazard assessments — basin depth and seismic shear velocity in shallow soil — are actually not always the best predictors of shaking amplification. This could mean underestimates of the shaking that large buildings would experience.

Ridgecrest shook L.A.

During the Ridgecrest earthquake, high rises experienced significant motion but not much damage. Though the basin is as deep as six miles (nine kilometers) beneath downtown L.A., the greatest shaking amplification was seen in West L.A. and the San Fernando Valley.

“We thought the largest amplification would be in the deepest part of the basin, but it turns out that oversimplifies things,” explains Kohler.

“It’s fascinating — for years we’ve been talking about amplification from the very deep basin in L.A. This potentially changes our thinking,” says Robert de Groot, Coordinator for Communication, Education, and Outreach at the U. S. Geological Survey ShakeAlert Earthquake Early Warning System Program. He says that cutting-edge research like this is always being incorporated into early warning technology, and is likely to inform future updates to those systems.

In the event of a future earthquake like Ridgecrest, a high-rise building in those areas could experience shaking four times larger than a building located in downtown Los Angeles, and eleven times what is felt on the bedrock surrounding the basin. In a 52-story building, this could mean as much as three feet (one meter) of swaying on the upper floors, and as much as two meters in a magnitude-7.6 earthquake, which would strain the building’s structural integrity.

Building to withstand shaking

The study has important implications for building codes, as the long-amplitude waves can affect high-rises as well as large fuel storage facilities and long-span bridges. “The building code currently has a very simplified version of what basin effects are, so we want to show how they should be modified or expanded upon for the next generation of codes,” says Kohler.

While this is a big step toward better hazard assessment in the L.A. Basin, many questions remain unanswered. Would a different earthquake produce the same shaking patterns observed during Ridgecrest? Kohler says that the 2010 magnitude-7.2 El Mayor-Cucapah earthquake produced similar patterns. Santa Monica in West L.A. — both within this study’s high amplification area — took heavy damage during the 1994 Northridge quake. This hints that the pattern observed from the Ridgecrest quake might be applicable to most others, but more data is needed.

A community seismometer array

The majority (360) of the seismic stations that recorded this data were part of the Community Seismic Network — a decade-long partnership between Caltech and the community to install these sensors. This project was a collaboration of civil engineers, seismologists and computer scientists. Most of the community sensors are placed in public schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District system. This network uses Raspberry Pis — credit card sized computers — to process the data at each site, and from there it is sent to the cloud.

Other cities on the West coast would benefit from deploying this type of dense seismic network — shaking from big earthquakes in cities like San Francisco and Seattle is also affected by basin amplification, but without dense data provided by hundreds of sensors, those effects are not as well understood.

“There are no down sides to this, it’s just a matter of getting the funds. Seattle is one example of a seismically active region that is really in need of more stations like this,” says Kohler.

Check your earthquake risk at Temblor.

Further Reading

Kohler, M. D., Filippitzis, F., Heaton, T., Clayton, R. W., Guy, R., Bunn, J., & Chandy, K. M. (2020). 2019 Ridgecrest Earthquake Reveals Areas of Los Angeles That Amplify Shaking of High‐Rises. Seismological Research Letters.

- Introducing Coulomb 4.0: Enhanced stress interaction and deformation software for research and teaching - February 20, 2026

- Deep earthquake beneath Taiwan reveals the hidden power of the Ryukyu Subduction Zone - January 7, 2026

- Magnitude 7 Yukon-Alaska earthquake strikes on the recently discovered Connector Fault - December 8, 2025