After months of heightened earthquake activity, Earth’s largest volcano has erupted for the first time in 38 years. Previous eruptions of Mauna Loa can give scientists some clues as to what this volcano has in store for Hawai’i.

By Melissa Scruggs, Ph.D. (@VolcanoDoc)

Citation: Scruggs, M., 2022, Earth’s largest volcano has started erupting. What might we expect?, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.286

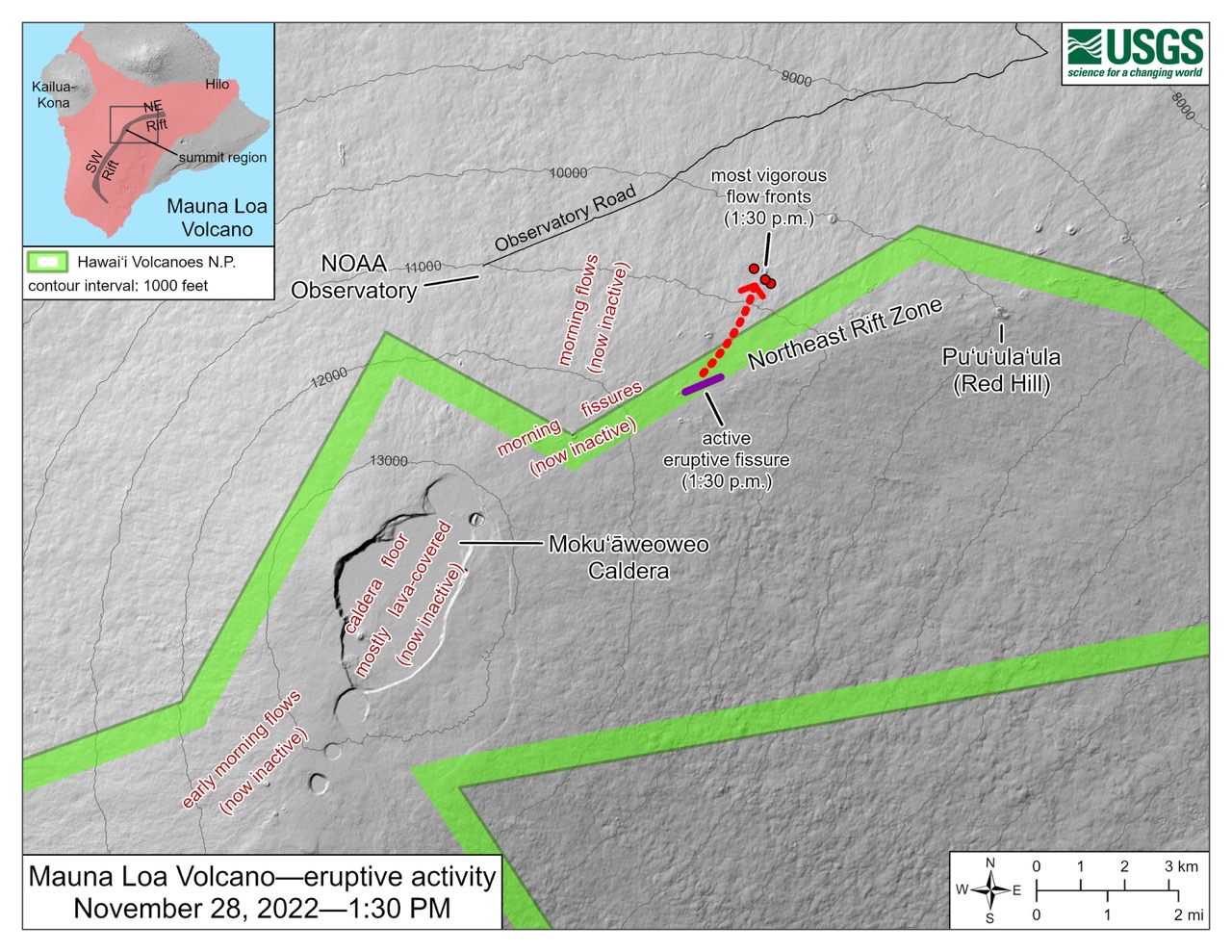

After 38 years of quietly overlooking its very active sister volcano Kīlauea, Mauna Loa volcano on the Island of Hawai’i (otherwise known as the Big Island) has reawakened. On Nov. 27, 2022, lava began erupting from a fissure inside of Moku’āweoweo Caldera at 11:30 p.m. (09:30 GMT, 11/28/2022), marking the first eruption of Mauna Loa to be surveilled in near-real time using modern volcano monitoring techniques. After seven hours of fissure eruptions in the summit caldera, activity relocated to the Northeast Rift Zone, where three fissures fed lava flows that traveled northward a few miles, and then stalled. Activity at the first two fissures lasted for another few hours, and by 1:30 p.m. only Fissure 3 continued to erupt effusively. Lava fountained as high as 200 feet (60 meters), but most of the fountains are only tens of feet (a few meters) tall.

At 7:30 p.m. (05:30 GMT on Nov. 29), a small fourth fissure opened near Fissure 3, and as of Tuesday evening, advancing lava flows remained about 4.5 miles (7,200 meters) away from Saddle Road, the road that bisects the Big Island. According to Ken Hon with the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, these new lava flows are following a similar path as flows from an eruption in 1935-1936 — but as is the nature of volcanism, nothing is set in stone, and we don’t know yet if the flows will continue to follow that path.

The most recent alert from the Hawaii Volcano Observatory advises there is currently no threat from lava flows to communities downslope of the Northeast Rift Zone, but because conditions during the beginning stages of an eruption can change rapidly, readers should stay tuned to information from the U.S. Geological Survey or the Hawaiian Department of Civil Defense.

This “sleeping giant” hasn’t always been quiet

With an estimated volume of 19,000 cubic miles (80,000 cubic kilometers), Mauna Loa accounts for more than half of the area of the Big Island and is the largest single volcano on Earth. Although the summit caldera is located 13,679 feet (4,169 meters) above sea level, the base of the volcano meets the ocean floor another 16,400 feet (5,000 meters) below the ocean’s surface. Mauna Loa is so large that its weight presses down on the ocean floor, displacing the crust another 26,200 feet (about 8,000 meters).

Mauna Loa is just one of five volcanoes — Kohala, Hualālai, Mauna Kea, Mauna Loa and Kīlauea — that make up the Big Island. The island and the rest of its namesake archipelago are built from hot spot volcanoes, formed as a tectonic plate passes over a mantle plume — a hot buoyant bit of Earth’s mantle that melts as it rises upward, bringing magma to the surface.

Lavas erupted within the last 4,000 years cover almost 90 percent of the volcano’s surface, but not all Mauna Loa eruptions are identical. Mauna Loa eruptions typically start in the summit caldera, and sometimes activity will relocate to either the Northeast or Southwest Rift Zone. Because the southern and western slopes of Mauna Loa are much steeper than the north and eastern flanks, lavas that erupt from vents along the Southwest Rift Zone can race downhill at speeds up to 6 miles per hour — leaving little warning for people to evacuate. This was the case in 1950, when lava flows reached the ocean in just three hours, cutting off access to parts of the island and destroying dozens of buildings. Lavas erupted from the Northeast Rift Zone usually do not travel as fast, as the slope is more gradual. Although it is possible that lava flows from the Northeast Rift Zone could eventually threaten nearby towns, it would take much longer for them to do so. For example, when vents along Mauna Loa’s Northeast Rift Zone erupted in 1880, it took nine months for lava flows to come within a mile of the city of Hilo.

Despite not erupting for nearly 40 years, Mauna Loa has been quite active in recorded history — erupting 39 times since record-keeping began in the early 19th century. Historically, Mauna Loa eruptions tend to last only a few weeks, but in rare cases may go on for a few years. Before 1950, Mauna Loa erupted about every five years or so. After the Southwest Rift Zone erupted in 1950, the behavior of the volcano changed and Mauna Loa erupted only twice more during the 20th century: in 1975 and again in 1984. The 1984 eruption began with a single-day fissure eruption in the summit caldera, and then migrated downrift along the Northeast Rift Zone, where lava flows continued to advance for three weeks and came within four miles of Hilo by the time the eruption was over.

What is causing this eruption?

Since 1984, a body of magma that underlies Mauna Loa, between about 2.5 to 8 kilometers (1.5 to 5 miles) depth, has been slowly and unsteadily refilling. During that time, several large seismic swarms — clusters of numerous small earthquakes that occur in quick succession — struck, likely caused by the accumulation of magma. The addition of magma to a storage reservoir can change how stress is distributed inside the body of the volcano, which can cause earthquakes. One hypothesis is that these earthquakes can “unclamp” the rift zones, allowing magma to travel upward and erupt.

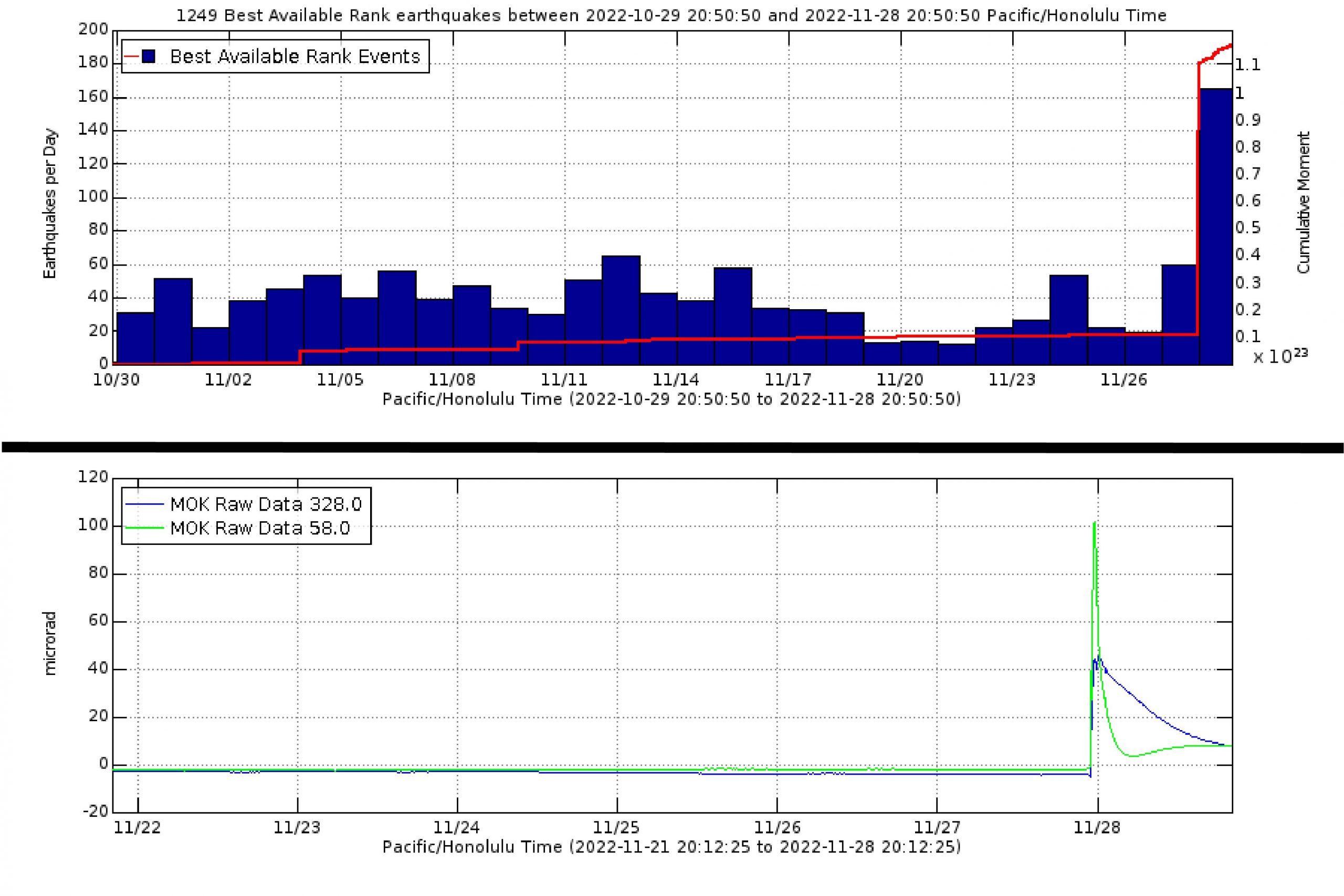

Short-lived seismic swarms beneath the Mauna Loa summit had become more commonplace in recent years, but increased drastically in mid-September 2022. During the month of November, between 20 and 60 earthquakes shook the summit region daily, with the majority around magnitude 2 and the largest being magnitude 4.2. Ground deformation measurements display an overall trend of inflation for Mauna Loa’s summit reservoir, suggesting that lava had been accumulating since at least December 2018.

Although scientists do not yet know exactly what triggered this new eruption, ground deformation records of Mauna Loa’s summit show that rapid inflation occurred just before the eruption began. It is possible that the cumulative effects of the several hundred recent earthquakes made conditions favorable for magma to ascend, triggering the 2022 eruption.

Is this related at all to activity at Kīlauea Volcano?

The short answer is: probably not. Both Kīlauea and Mauna Loa are fed by the Hawaiian hot spot. Scientists think there may be some very deep connection between the two volcanoes because when magma supply from the hot spot doubled between 2003 and 2007, the ground at both Mauna Loa and Kīlauea inflated (indicating that magma was being delivered into both volcanoes from the mantle). A study published earlier this month in Nature Scientific Reports found a geodetic relationship between the two volcanoes: When magma accumulates in Mauna Loa’s shallow reservoir and the ground inflates, stresses from the increase in volume can hamper the ascent of magma into the Kīlauea summit reservoir, making an eruption of Kīlauea less likely. At this moment, however, both volcanoes are erupting. Kīlauea’s eruption is confined to Halema’uma’u Crater at its summit.

Mauna Loan lavas have a different geochemical signature than lavas from Kīlauea Volcano. Mauna Loa’s lavas are also less viscous, or runnier. So, even though Kīlauea is built on the southeastern flanks of Mauna Loa, scientists generally agree that the two have separate magma plumbing systems. Thus, it’s very unlikely that this eruption is related to Kīlauea Volcano’s current lava lake activity.

What can we expect to happen next?

As of the writing of this article, the active lava flow does not appear to pose any hazard to the residents of Hawai’i. The eruption is ongoing, and activity is not expected to renew in either the summit caldera or at the rift zone upslope of the currently active fissure. The gentle slopes of the Northeast Rift Zone result in slowly advancing lava flows, which will usually travel hundreds to thousands of feet per day, as long as magma continues to be supplied to the fissure opening.

Lava flows are just one of the volcanic hazards produced by an eruption, however. Poor air quality may affect island residents and tourists downwind of active fissures, as volcanic ash (microscopic bits of fragmented glass formed by lava during an eruption), Pele’s hair (long, very thin strands of volcanic glass that form during Hawaiian-style eruptions) and vog (hazy air pollution caused by the emission of volcanic gases) can be transported long distances depending on weather patterns. Vog and wind forecasts are updated daily on the Hawaii Interagency Vog Information Dashboard.

Scientists look to a volcano’s past behavior for clues as to how a current eruption might proceed. If this new eruption at Mauna Loa behaves similarly to past events, activity should remain along the Northeast Rift Zone. However, there is no telling how long the eruption will last, or if it will continue to follow the same eruption patterns as before. Only time will reveal Mauna Loa’s secrets.

- Deep earthquake beneath Taiwan reveals the hidden power of the Ryukyu Subduction Zone - January 7, 2026

- Magnitude 7 Yukon-Alaska earthquake strikes on the recently discovered Connector Fault - December 8, 2025

- Upgrading Tsunami Warning Systems for Faster and More Accurate Alerts - September 26, 2025