Questions remain about the cause of the eruption and subsequent tsunami, which damaged nearby islands in Tonga.

By Marie Edmonds, Ph.D., University of Cambridge

Citation: Edmonds, M., 2022, Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai in the south Pacific erupts violently, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.231

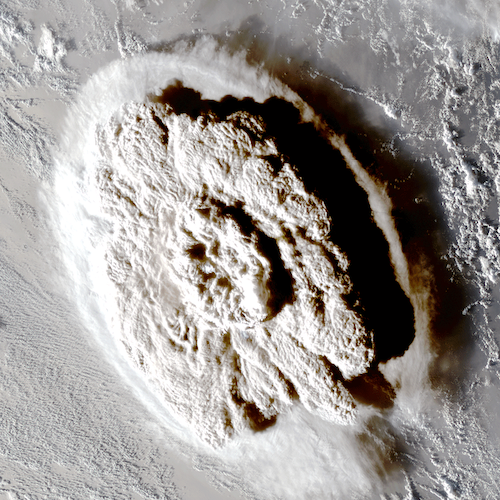

The Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai volcano, 40 miles (65 kilometers) north of Tongatapu, Tonga, erupted on January 15 at 5:14 p.m. local time, triggering tsunami waves that swept across the Pacific. The energy released in the eruption was equivalent to a magnitude-5.8 earthquake at the surface, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. The powerful eruption was captured on satellite images, which show a shock wave and a rapidly expanding ash cloud that reached 12 miles (20 kilometers) into the atmosphere.

News of the immediate impact of the eruption on the Tongan islands has been slow to emerge because internet communications have been entirely cut off by the eruption. It is likely, however, that the islands have experienced many inches of ash fall as well as damage from the tsunami, which inundated coastal areas and reached a height of 2.7 feet (83 centimetres) in Nuku’alofa, according to the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center.

Tsunami waves reached 3.6 feet (1.1 meters) along the northeastern coastline of Japan at a port in Kuji, Iwate (Source: Japan Meteorological Agency) and up to 3.6 feet (1.1 meters) in Port San Luis, California (Source: NOAA). In northern Peru, two people drowned when waves inundated a beach in the Lambayeque region.

Explosion detected on the other side of the world

The eruption was heard in New Zealand. The shock wave was violent enough to shake houses in Fiji, more than 450 miles (720 kilometers) away from Tonga.

Pressure surges from the atmospheric perturbation caused by the eruption were felt right across the world. Atmospheric pressure fluctuations have been reported in New Zealand, the U.S., Brazil, Japan and Europe. More than 14 hours after the eruption, the UK Meteorological Office picked up several pressure waves, more than 10,000 miles away from the volcano. The agency described the waves as “like dropping a pebble in a still pond and seeing the ripples.”

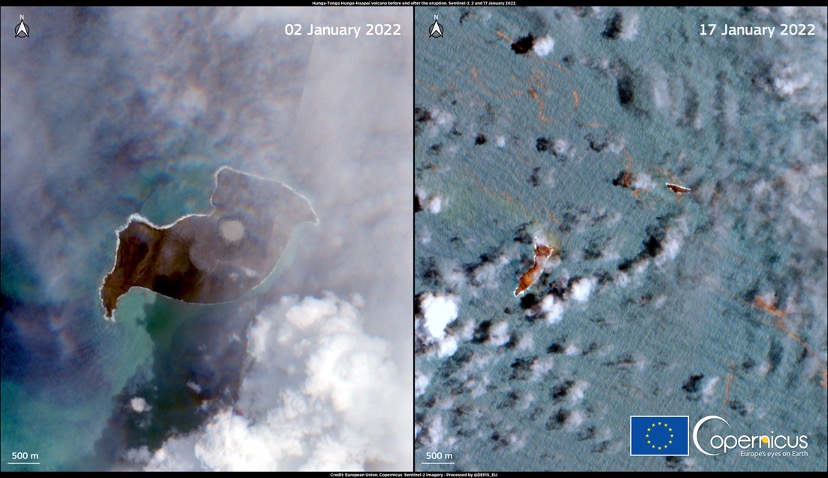

The eruption was so powerful it destroyed the subaerial part of the volcano that had been built up in successive eruptions since 2015, according to the Smithsonian’s Global Volcanism Program. Radar images of the island acquired by European Space Agency’s (ESA) Sentinel-2 satellite show that the island has largely disappeared following the eruption; only the far southwestern and northeastern tips of the island remain.

Long-term climate impacts unlikely

The ash produced by the eruption has now dispersed from the caldera, but the finest particles are likely still aloft high in the atmosphere and will remain there for months or even years.

The eruption also produced around 0.4 teragrams of sulfur dioxide (SO2), according to spectrometer data from ESA’s Sentinel 5P satellite. Past large explosive eruptions have typically been associated with global cooling. SO2 injected into the stratosphere — the second layer of the atmosphere — forms sulfate aerosol when it reacts with water, which absorbs and scatters incoming radiation from the sun, thereby cooling the Earth’s surface.

Here are the latest #Sentinel5P #TROPOMI SO₂ data covering most of the #HungaTongaHungaHaapai #eruption cloud (just the western edge is missing). The total SO₂ mass is ~0.4 Tg. @CopernicusEU @DlrSo2 @BIRA_IASB @ESA_EO @esa pic.twitter.com/sWNOhIQkcw

— Prof. Simon Carn (@simoncarn) January 16, 2022

The 1991 eruption of Pinatubo Volcano in the Philippines emitted around 18-19 teragrams of SO2, which caused cooling of a few tenths of a degree for a few years. It is unlikely that the SO2 emitted from the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai eruption will significantly impact the climate.

One volcano in a chain

The Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai volcano lies along the Tonga-Kermedec Arc, where two tectonic plates in the southwest Pacific converge. This volcano is one of a chain of largely submarine volcanoes that extend all the way from New Zealand in the southwest to Fiji in the north-northeast. Here, the Pacific plate subducts beneath the Indo-Australian plate. As it sinks, the Pacific Plate heats up, releasing fluids into the overlying rocks, which causes them to melt. The magma rises into the overlying crust and some erupts at the surface. Eruptions from subduction zone volcanoes are notoriously explosive because magmas there are sticky and contain large quantities of dissolved water from the mantle, which is the explosion’s “fuel.”

For submarine volcanic eruptions however, there is an added ingredient that causes them to be extra-violent. During large volcanic eruptions a caldera, or large depression on the surface, can form due to the void left in the ground by the erupted magma. Calderas that form on the seafloor can cause tsunamis and large earthquakes when large rock masses sink during the eruption.

Seawater can flow into the faults and fractures that form around the edges of the caldera. If water comes into contact with hot magma, it flash boils into steam, which expands rapidly, adding to the explosive power of an eruption. Such eruptions are termed “hydrovolcanic.” They generate powerful base surges — or pyroclastic flows — that expand out from the base of the eruption column, and can travel long distances. A famous example is the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa Volcano in Indonesia. The sound of the explosion was heard 1,800 miles (3,000 kilometers) away. Large tsunami waves and pyroclastic surges that travelled 25 miles (40 kilometers) over the surface of the sea killed more than 36,000 people.

Geologists studying the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai volcano have uncovered its few-thousand-year-long history of eruptions just like the one that occurred on January 15. The volcano erupted explosively in 2009 and in 2014-2015, producing ‘Surtseyan’ eruptions — a smaller magnitude explosive eruption produced by the interaction of magma and seawater. The precise magnitude of this latest eruption will be known once the height of the eruption column as well as the volume of erupted material is estimated, but it is certainly one of the most significant eruptions of the 21st century thus far.

Answers still to come

There are many questions to be answered over the coming weeks and months about the mechanisms and impacts of this eruption. Immediate questions concern the fate of the residents of Tonga, who are contending with the enormous challenges of the aftermath of the eruption and tsunami, including missing loved ones, enormous infrastructure damage, thick ash cover, contaminated drinking supplies and a lack of basic medical and communication services.

There will be detailed studies of the geophysical signals accompanying the eruption and the period leading up to it to better understand how the eruption was triggered and its magnitude. Scientists will be particularly interested in infrasound, satellite-based data and eventually will study the volcanic deposits and landforms produced. In particular, scientists will seek to understand the geological sequence of events that led to the simultaneous explosion and tsunami that had such wide-ranging effects across the Pacific Ocean.

References

Guo, S., Bluth, G. J., Rose, W. I., Watson, I. M., & Prata, A. J. (2004). Re‐evaluation of SO2 release of the 15 June 1991 Pinatubo eruption using ultraviolet and infrared satellite sensors. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 5(4).

- The Earthquake that Shook the South - February 26, 2026

- Introducing Coulomb 4.0: Enhanced stress interaction and deformation software for research and teaching - February 20, 2026

- Deep earthquake beneath Taiwan reveals the hidden power of the Ryukyu Subduction Zone - January 7, 2026