A group of social scientists, seismologists and engineers is developing surveys to understand the efficacy of earthquake early warning alerts.

By Meghomita Das, Palomar Fellow (@meghomita)

Citation: Das, M., 2023, Harnessing citizen science helps develop efficient earthquake early warning, Temblor, http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.292

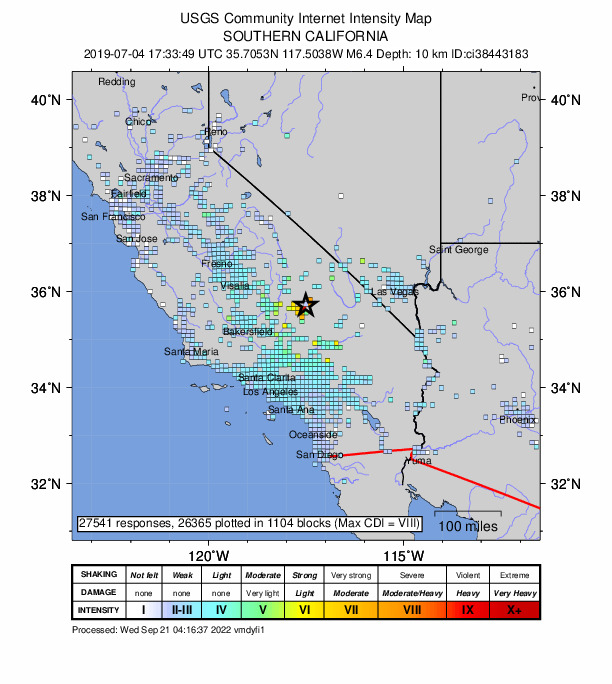

Within hours following the magnitude-6.4 Ridgecrest earthquake on July 4, 2019, the U.S. Geological Survey’s global earthquake reporting platform, Did you feel it? (DYFI), was bombarded with 27,534 responses. Many reports described a shaking intensity of VIII, or severe, on the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale, in some places. Two days later, a magnitude-7.1 earthquake struck the same area with 24,386 DYFI responses describing the shaking intensity felt by those near the epicenter.

The responses provided scientists with vital information about the shaking and damage caused by both earthquakes, and helped scientists generate shaking intensity maps after the events. However, with the relatively recent implementation of Earthquake Early Warning systems along the West Coast of the United States, scientists are trying to adapt the reporting system to help them understand just how effective this system really is. They’re also trying to develop better and more engaging earthquake awareness and outreach programs for the public.

For a recent study presented at the AGU 2022 Fall Meeting, a team of researchers developed a companion questionnaire to the DYFI reporting system to assess how people respond to Earthquake Early Warning alerts. Of particular interest is what actions people take to protect themselves after receiving the notification.

The new questions are in addition to the standard ones asked in the DYFI report, which include information about the intensity of shaking and location of the person filling out the form.

“We get to know the shaking intensity at the location of each observer from DYFI,” says David Wald, a seismologist at the USGS and a co-author of this study. “But an important next step is to understand the human behavior in response to Earthquake Early Warning messages, and ask what did [the alert] mean, how did you respond to the alert, how much time did you have to respond before the shaking.”

Did you feel it? Version 2.0

The DYFI questionnaire and reporting system was first developed by the USGS in 1997 for domestic use, and then implemented globally in 2004. The purpose of DYFI is to rapidly collect information from Internet users about the shaking and damage experienced during an earthquake. This information helps to generate intensity maps immediately following a temblor.

The respondents answer questions pertaining to the environment they were in during the event (e.g., tall or short building), the intensity of shaking they experienced, their specific geographical location during the event, their reaction (e.g., whether frightened or excited), and the protective actions they took during the earthquake. Since its inception, the DYFI system has generated thousands of earthquake intensity maps from the information contributed by more than 4 million respondents. While providing a wealth of information, the DYFI currently lacks questions that would allow behavioral scientists and developers of Earthquake Early Warning systems to gauge how recipients of earthquake alerts respond.

“[The new survey] will serve most readily where there are more people experiencing Earthquake Early Warning alerts,” says Wald. Tying in the new companion questions to the existing DYFI questionnaire would mean that the USGS already has the attention of people who felt an earthquake and are willing to report on their perception of the event. Asking questions about the alert and associated response is a natural extension for this captive audience.

Integrating Earthquake Early Warning systems with behavioral sciences

For people living along the U.S. West Coast, the current Earthquake Early Warning system is called ShakeAlert. ShakeAlert consists of a network of seismic stations that rapidly detects earthquakes. If an earthquake is verified and above a threshold magnitude, a ShakeAlert message will be delivered to the population expected to feel shaking via distribution partners like MyShake and other downloadable apps, FEMA’s Wireless Emergency Alert system, and Android Earthquake Alerts. These alerts prompt recipients to take protective action — Drop, Cover, and Hold On, or DCHO.

The user survey that this study aims to provide will improve the functionality of ShakeAlert, Wald and his colleagues suggest. However, due to the global nature of DYFI reporting, the questions asked in the survey will pertain to any Earthquake Early Warning system available wherever an earthquake strikes, with specific mentions about ShakeAlert only for residents of the western U.S.

Some of the questions that will be part of the new survey include whether the recipient received the alert before, during or after the earthquake, how many seconds the user had to take protective action, and whether the user found the alert useful. These and other questions will help scientists better understand what actions a user might take when they receive the alert.

The survey will close out with demographic information that the current DYFI lacks. Demographic information is essential because it shows whether gender, age and educational level influence behavior during earthquakes.

“I think having these surveys is essential and critical as we are trying to understand how people use these alert systems,” says Carson MacPherson-Krutsky, a geoscientist and research associate at the Natural Hazards Center and at Boise State University who was not associated with this study.

Currently, the new questions have been approved for implementation, and must be integrated into the DYFI reporting system. The updated questionnaire will be available in both English and Spanish. Based on the responses from this survey, the researchers also plan to explore the effectiveness of current earthquake awareness and outreach programs, such as ShakeOut. The data can help scientists adapt such programs in a way that will promote protective actions.

Meghomita Das is Temblor’s Palomar Fellow. She is a Ph.D. candidate at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, where she studies the signals of ancient earthquakes and slow slip events (www.meghomita.com). Palomar Holdings is sponsoring a science writing fellow to cover important earthquake news across the U.S.

Further Reading

Goltz, J. D., Wald, D. J., McBride, S. K., DeGroot, R., Breeden, J. K., & Bostrom, A. (2022). Development of a companion questionnaire for “Did You Feel It?”: Assessing response in earthquakes where an earthquake early warning may have been received. Earthquake Spectra, 87552930221116133.

- The Earthquake that Shook the South - February 26, 2026

- Introducing Coulomb 4.0: Enhanced stress interaction and deformation software for research and teaching - February 20, 2026

- Deep earthquake beneath Taiwan reveals the hidden power of the Ryukyu Subduction Zone - January 7, 2026