Quake Insight | Feb 22, 2016

Over 5 years since the Canterbury Earthquake Sequence started, the city of Christchurch is still being rattled by large aftershocks.

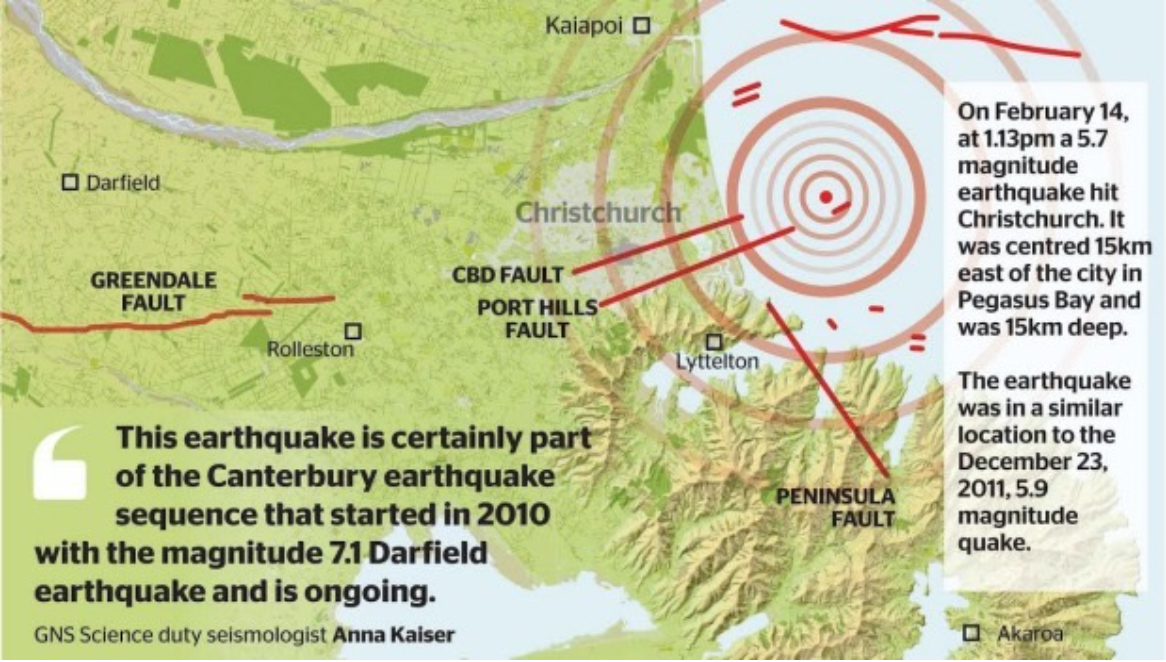

The magnitude 5.7 earthquake, which was centered 15 km east of Christchurch, at a depth of 15 km, not only brought more damage, but memories of nearly five years ago when a deadly quake shook the city. This most recent event, which was located offshore in the Pacific Ocean, was felt to varying degree throughout New Zealand’s South Island. It was also the largest earthquake in the area since a magnitude 5.9 on December 23, 2011, which had a similar epicenter. Based on this data, the earthquake likely involved slip on an oblique thrust fault, and means the earthquake sequence which began in September 2010 is still ongoing.

Distribution of Damage and Degree of Shaking Highlights Earthquake Complexity

While the magnitude of this earthquake was not as large as some that have hit the region, because the epicenter was shallow, intense shaking was felt, and the city experienced more damage and liquefaction. The iconic Christchurch Cathedral, which was severely damaged in 2011, and is undergoing demolition, lost more of its façade, and eastern suburbs once again had to deal with liquefaction. Additionally, cliffs collapsed along the coast, creating large dust clouds, and forcing people to run for shelter. For some residents in the area, including friends of mine, every shake brought down more rocks which was unnerving.

The recurrent liquefaction in the eastern suburbs highlights how certain areas can be much more prone to certain geologic hazards. Though more detail will be explained in a series of Temblor blog posts titled “Living with Liquefaction” much of this susceptibility can be attributed to near-surface geology. Even subtle differences in sediment coarseness can significantly impact whether or not liquefaction will occur. For example, in some neighborhoods in Christchurch, houses are built on ancient dune sand, while others are on more modern silty river channels. In this instance, the river channel deposits would be more prone to liquefaction. This varying geology, sometimes separated by only feet, is one of the reasons why liquefaction can be so variable.

Just as liquefaction was site-specific so was shaking. Though shaking was deemed “severe” by GNS Science, through both talking to people and reading reports, the way in which it was felt varied significantly throughout the city. Some say there was a bang, followed by a bit of rolling, while others say it lasted for about 20 seconds with rolling only getting stronger and stronger.

Having both experienced and studied earthquakes in Christchurch, it seems safe to say that the same near-surface geology which impacted where liquefaction occurred, also influenced the way shaking was felt. In fact, the two are related. In areas where liquefaction was present, rolling likely dominated and lasted for longer periods of time, due to shallow water tables and near-surface silty deposits. Such a combination could prolong the rolling and feel as if you were sitting on a waterbed. While not exactly this cut-and dry, there is a definite relationship between near-surface geology, and the shaking experienced during an earthquake.

Looking Forward

Following this most recent event, residents of the Garden City had memories of the deadly February 22, 2011 earthquake brought back to the forefront. However, what it also did was illustrate that an earthquake sequence can last for extended periods of time. Even though this sequence started over 5 years ago, large earthquakes still occur, and GNS Science estimates that there is a 63% chance (Up from 49%) of another magnitude 5.0-5.9 earthquake occurring in the next 12 months. Because of this, it seems right to say to the city of Christchurch “Kia Kaha,” a Māori phrase meaning “stay strong” which became iconic following the February 2011 earthquake.

David Jacobson, Researcher, Temblor, Inc.

Sources Include: GNS Science, Stuff.co.nz, One News New Zealand, Recurrent liquefaction in Christchurch, New Zealand during the Canterbury earthquake sequence, Geology 41 (4) p. 419-422, Bastin, S., Quigley, M.C., Bassett, K. (2015) Comparison of liquefaction-induced land damage and geomorphic variability in Avonside, New Zealand, 6th International Conference on Earthquake Geotechnical Engineering, 1-4 November 2015, Christchurch, New Zealand

- Deep earthquake beneath Taiwan reveals the hidden power of the Ryukyu Subduction Zone - January 7, 2026

- Magnitude 7 Yukon-Alaska earthquake strikes on the recently discovered Connector Fault - December 8, 2025

- Upgrading Tsunami Warning Systems for Faster and More Accurate Alerts - September 26, 2025