La versión en español de la publicación del blog se puede encontrar aquí

Click for the New Ecuador Earthquake Article

17 April 2016 | Quake Insights

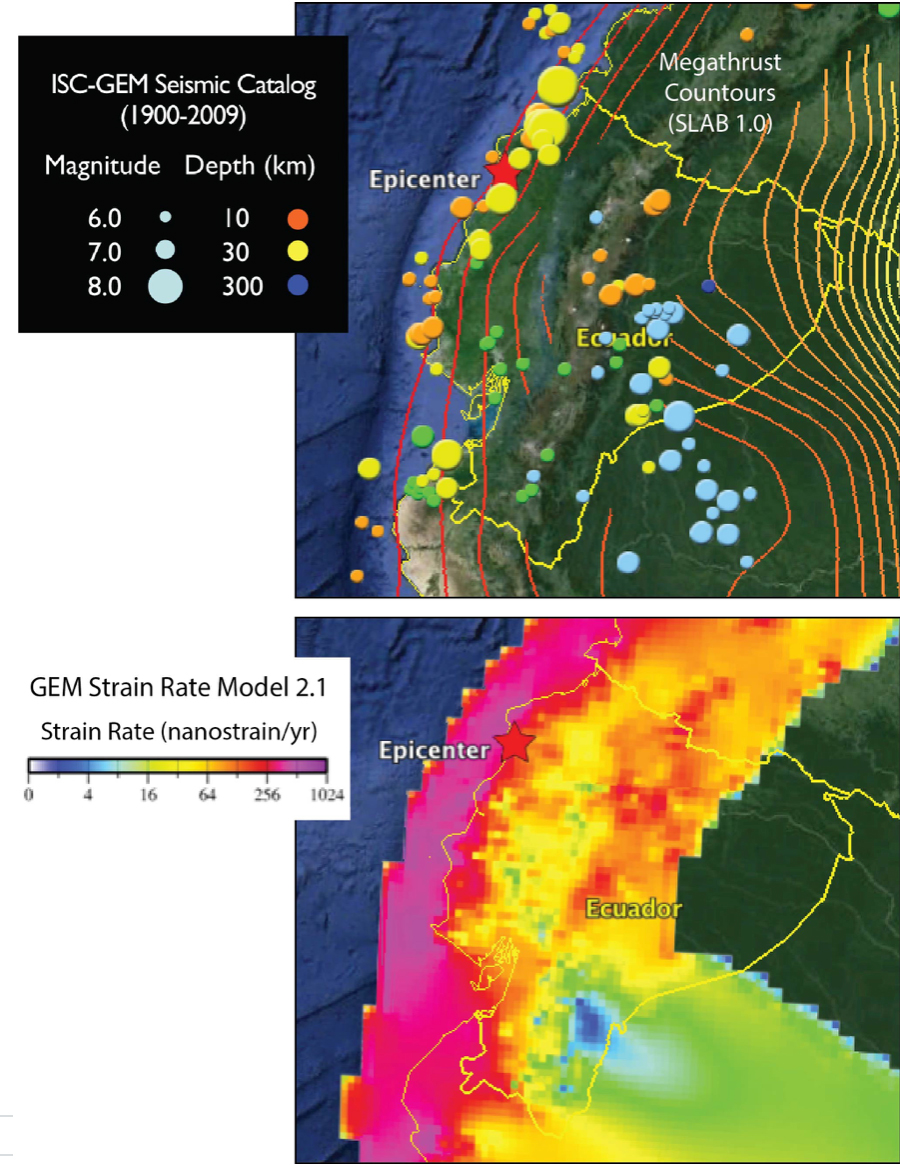

The event severely shook the coastal cities of Muisne, Tosagua, and Pedernales, with 34,000 inhabitants. The quake was broadly felt throughout Ecuador and southern Colombia. On the basis of historic earthquakes, including the 1906 M~8.3 shock, as well as a high strain rate, the region was known to have a high seismic hazard.

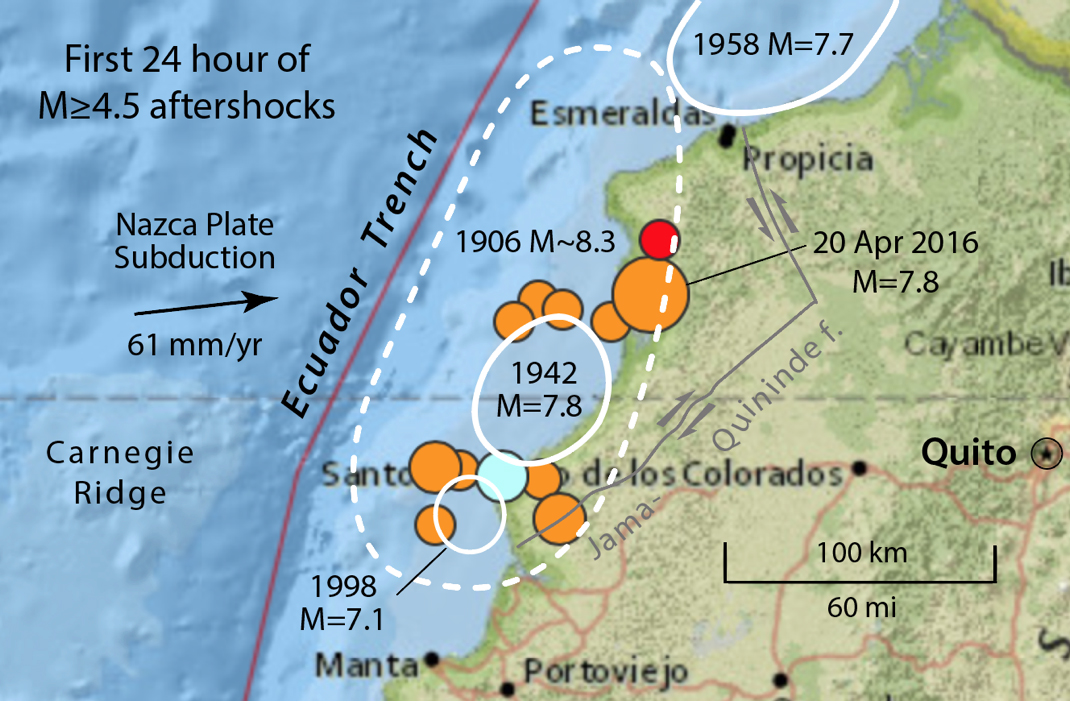

The megathrust ruptured along the Ecuador Trench, along which the Nazca plate subjects beneath South America at about 55-61 mm/yr. The rupture area, as determined thus far only by Gavin Hayes at the USGS in Golden, CO, using seismic waveforms, is about 50 x 100 km in extent (30 x 60 mi), and is inclined (‘dipping’) at about 15° under the coastline. The rupture propagation took about a minute, with the greatest pulse in the first 30 seconds. The peak slip is about 5 m (16 ft), directly under the coastline. The shallow depth, rapid rupture, and high slip beneath populated areas probably all contributed to the damage, which thus far has killed 238, and will likely rise considerably.

The 16 April 2016 quake appears to lie in almost the exact location as the 1942 M=7.8 quake studied by Senneson and Beck (1998). The distribution of observed seismic intensities for the 1942 shock closely match those predicted by the USGS for yesterday’s quake, and their aftershock distributions are similar. In addition, the large aftershocks of the 16 April 2016 shock lie on either side of the 1942 rupture zone. This would be expected if the 2016 rupture were smooth (rather than spiky), with aftershocks in the Coulomb stress ‘butterfly zones’ just outside of the rupture patch.

There is also evidence that 50 km to the south of the 2016 M=7.8 quake, there was a ‘slow slip event,’ essentially a M=6.3 silent earthquake. This event is shown in the figure below from Chlieh et al. (2014); the event can only be detected by GPS receivers because it did not excite any seismic waves. Many subduction zones produce such slow slip events. It is possible that theses events, if frequent enough, relieve the stress that would otherwise accumulate to produce great quakes.

Is a repeat of the 1942 event reasonable, given that only 75 years has since elapsed?

The answer is yes. At the 60 mm/yr subduction rate, 75 years is enough to produce another quake with 4-5 m (12-16 ft) of slip. Given the area of the two shocks, a M=7.8 today would be right on target if the site did not suffer much larger quakes at other times. But that’s the problem: The site did suffer a M~8.3 event in 1906, and so repeats of M=7.8 events cannot be the whole story. Near-exact repeats of earthquakes are very rare; in general, we find a wide diversity of rupture behavior. And considering that this site was part of the ten-times larger event in 1906, it is particularly baffling.

What next?

A subsequent M~8 event to the south might be considered unlikely, both because of the M=7.1 event in 1998 and the slow slip event in 2010. But the region to the north of the 16 April 2016 event is different. There is an 80 km (50 mi) region that has not ruptured since 1906 that would seem able to host another M~7.8 shock. Further, there is the right-lateral Jama-Quininde fault, parts of which could have been brought closer to Coulomb failure by this recent 2016 megathrust event. Both should now be closely watched.

Click for the New Ecuador Earthquake Article

Ross Stein and Volkan Sevilgen, Temblor

Sources: USGS, GEM Foundation (globalquakemodel.org), and,

Chlieh, M., P.A. Mothes, J.-M. Nocquet, P. Jarrin, P. Charvis, D. Cisneros, Y. Font, J.-Y. Collot, J.-C. Villegas-Lanza, F. Rolandone, M. Vallée, M. Regnier, M. Segovia, X. Martin, H. Yepes (2014), Distribution of discrete seismic asperities and aseismic slip along the Ecuadorian megathrust, Earth Planet. Sci. Letts., 400, 292-301, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2014.05.027

Collot, J.-Y., B. Marcaillou, F. Sage, F. Michaud, W. Agudelo, P. Charvis, D. Graindorge, M.-A. Gutscher, and G. Spence (2004), Are rupture zone limits of great subduction earthquakes controlled by upper plate structures? Evidence from multichannel seismic reflection data acquired across the northern Ecuador–southwest Colombia margin, J. Geophys. Res., 109, B11103, doi:10.1029/2004JB003060.

Sennson, Jennifer L, and Susan L. Beck (1996), Historical 1942 Ecuador and 1942 Peru subduction earthquakes and earthquake cycles along Colombia-Ecuador and Peru subduction segments Pure Appl. Geophys., 146, 67-101, doi: 10.1007/BF00876670

- Earthquake science illuminates landslide behavior - June 13, 2025

- Destruction and Transformation: Lessons learned from the 2015 Gorkha, Nepal, earthquake - April 25, 2025

- Knock, knock, knocking on your door – the Julian earthquake in southern California issues reminder to be prepared - April 24, 2025